Union Notables

- Title

- Union Notables

- Description

- Union Notables is a celebration of the great men and women who have studied and worked at Union from its founding in 1795 to the present day.

Items

-

Jackson, LeAta R.LeAta R. Jackson was the first woman of color to receive Union College's Bailey Cup award. The Bailey cup was established in 1912 and is awarded to a member of the senior class who has rendered the greatest service to the College in any field.

-

Robinson, ScharnScharn Robinson was the recipient of the Bailey Cup award two years later after the first woman of color, LeAta R. Jackson ('88), received the award.

-

Duvilaire, NadiaNadia Duvilaire was the first woman of color to win the Daggett Prize. The Daggett prize was established in 1897 by Josephine E. Daggett and is awarded annually to a senior for "conduct and character".

-

Walker, W. LorettaW. Loretta Walker was the first black woman with faculty status to receive tenure. She served in Schaffer Library as a librarian from 1968-1981, retiring as the Head of Information Services, Ms. Walker graduated from Howard University and received an M.A. from the College of St. Rose and Masters of Library Science from SUNY Albany.

-

Stout, KatherineKatherine M. Stout was the first woman officially admitted to Union College for undergraduate studies. She was described as "a top 10 percent scholar, track star, basketball player, sailplane pilot, musician, and girl." -Encyclopedia of Union History, page 797

-

Nott, Urania SheldonUrania Sheldon Nott was the third wife of President Eliphalet Nott. Prior to her 1842 marriage, she opened a private school for young ladies that eventually moved to Schenectady in 1830. It is likely Urania first met Nott in Schenectady through social connections, in particular Mary Hosford who taught at Urania's schools and married Jonathan Pearson, UC '35 in 1841. "Miss Sheldon has been for several years past, the principal of the Schenectady Female Seminary, which under her superintendence attained the highest rank as a school for the thorough and accomplished education of young ladies." -Schenectady Cabinet newspaper, March 24, 1837

-

Evans, Ruth AnneRuth Anne Evans was the first female faculty member to be named full professor in 1973, Ms. Evans worked as a librarian at the Schaffer Library from 1952-1989. Ruth Anne Evans was by all accounts one of the most accomplished librarians and one of the most knowledgeable college historians ever to work at Union College. As a librarian at the College for thirty-seven years, Evans earned a reputation by helping hundreds of students research topics from protozoa to the history of World War II. To many students and faculty, however, she was best known as the principal reference for anyone wanting to know anything about Union's history. As a colleague once said, "If Ruth Anne doesn't know it, it didn't happen."

-

White, KateKate White appeared on the cover of Glamour magazine in 1972 as one of the country's "Top Ten College Girls." Ms. White is a prolific author and has served as the editor in chief of Child, Working Woman, McCall's and Redbook Magazines.

-

Yates, Joseph ChristopherJoseph Christopher Yates was distinguished for “his plain and practical common sense, for his uprightness and impartiality, and for the courtesy and urbanity which gained him the respect and esteem of the public.” This assessment of Yates was based on his roles as a lawyer, statesman, politician, and founding trustee of Union College. Born on November 7, 1768 in Schenectady, NY to Colonel Christopher P. Yates and Jannetje Bradt Yates, he was the eldest son of seven children. When his father died in 1785 the executors of his estate were his brother, a farmer, and his widow Jannetje. On the subject of the Yates sons’ future, this – possibly apocryphal – anecdote survives: “Dey shall work,” said the farmer, “I am the axaceter.” “Dey shall be eddicated,” replied the widow, “I am the axectrix.” Fortunately for Union College, the City of Schenectady, and the State of New York, the widow prevailed. Yates studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1792. He became the first Mayor of Schenectady in 1798, at the age of thirty. From 1805 to 1807 Yates served a term as a New York State Senator during his tenure as Mayor of Schenectady. In 1808 he became a judge of the New York State Supreme Court, where he served for fifteen years. During this time, as a member of the Council of Revision, he cast a decisive vote in favor of the construction of the Erie Canal. His public service also included membership on the Board of Regents from 1812 to 1833. Yates was New York’s fourth Governor, and the only New York State Governor to come from Schenectady. He served for a single term, from 1823-1824: in an unusual twist, he succeeded Dewitt Clinton, and was then succeeded by Clinton. As Governor, Yates championed the idea of taking the power of electing a U.S. President out of the hands of the New York State legislature and giving it to the people. He proposed that the legislature pass a law allowing eligible voters to select electors who would in turn cast ballots for President of the United States. In support of his position he argued that “the people alone are the true and legitimate source of all power.” The home he inhabited in Schenectady while the Governor of New York still exists at 17 Front Street in the city's historic Stockade District. Governor Yates hosted the Revolutionary War hero General LaFayette at this home during the opening celebrations for the Erie Canal in 1825. Yates was the youngest member of the original Board of Trustees of Union, serving from 1795 until his death in 1837. Yates and his fellow board members persevered in their effort to found a college in Schenectady, in the face of challenges from the nearby community of Albany. The circumstances of his education had shown him the need of a seminary in upstate New York and he became active, even as a young man, in the movement that resulted in the founding of Union College. ...The prosperity of Union College was to him a matter of deep interest, and it may well be said the history of Union College is blended with that of Joseph Yates. Yates also served on a committee with Dirck Romeyn and others, to determine what books and instruments would form Union’s “first purchase” – the group of instructional materials deemed necessary to the educational mission of the new institution. After his political career ended in 1834, he practiced law from an office attached to his house at 17 Front Street, and helped found the Schenectady Savings Bank, an institution for which he served as President until his death in 1837.

-

Wright, AllenAmong the prominent nineteenth-century Union graduates, there are some whose names are still familiar today, such as Chester Arthur and William Seward. There are those, however, whose names and deeds are less well known, but whose lives and achievements were nevertheless important to their communities and to the nation. Allen Wright is just such an alum. His name is unfamiliar, except in Oklahoma, where he lived most of his life and whose name he coined. As a prominent member of the Choctaw Nation in the last half of the 1800s, Wright’s career and activities deserve wider recognition. Allen Wright was born in Mississippi in 1826. At birth, he was named Kiliahote (translation from Choctaw: “Come, let’s make a light.”) After the death of his mother in 1832, he and his father and the rest of the family left Mississippi and settled in what was then known as Indian Territory. Today it is McCurtain County, Oklahoma, located in the southeastern corner of the state. The family’s departure from Mississippi was undoubtedly part of the large-scale Indian removal mandated by President Andrew Jackson’s signing of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. This act authorized the removal of all Native Americans living east of the Mississippi River to territories to the west of the river. After his father’s death in 1839, Wright was sent to live with an uncle. He had previously attended a Choctaw mission school, where he was assigned English names, including the surname of Alfred Wright, a distinguished missionary working among the Choctaws. Allen Wright resumed his schooling in 1840, first at a mission school for four years and then at Spencer Academy. In 1848 the Choctaw Tribal Council selected Wright and four other Choctaw young men to attend colleges in the eastern United States. Initially enrolled at Delaware College, Wright transferred to Union College in 1850 and graduated in 1852. He obtained a Master’s degree in 1855 from Union Theological Seminary. Unfortunately, we have very little information about Wright’s time at Union. We do know that he took the usual courses in the Classical curriculum, which probably served him well when he translated parts of the Bible from Hebrew to Choctaw later in his life. He also enrolled in Eliphalet Nott’s senior course, called Kames. Nott himself obviously had an impact on the young man, as Wright named one of his sons Eliphalet Nott Wright, a member of the Union Class of 1882. Newly ordained as a Presbyterian minister, Allen Wright returned to Choctaw territory to teach at Armstrong Academy and to preach in the surrounding area. In 1857 he married Harriet Mitchell, with whom he had eight children. Meanwhile, Wright’s interests extended to farming and ranching, as well as tribal politics. Wright’s public career began in 1856 when he became a member of the Choctaw Council. The Choctaw tribal government was disorganized at this time so a new constitution was proposed in 1857. However, some felt it concentrated too much power in a single chief. Wright was one of those opposed to this constitution and worked to form a new constitution, which was adopted by the Choctaw in 1860. At both the beginning and the conclusion of the American Civil War, the Choctaw Nation authorized Allen Wright to sign treaties with the opposing governments – one to ally the nation with the Confederacy and the other to secure peace with the U.S. The latter involved Federal recognition of a multi-tribal council in Indian Territory, which Wright suggested be named “Oklahoma” Territory, from the Choctaw words “okla” (people) and “huma” (red). In 1866 and 1868, Allen Wright was elected Principal Chief of the Choctaws. Numerous intrigues and accusations surrounded his four years in office. Wright, however, seemed to have risen above them and been concerned primarily with the welfare and the “greatest good” of the Choctaw Nation. Allen Wright’s accomplishments are numerous: scholar, clergyman, soldier, and politician. He was not concerned with personal gain but, rather, with the well being of those around him – his family and the Choctaw Nation. Two of Wright’s sons, Eliphalet Nott Wright and Frank Hall Wright, attended Union College; the latter graduated in 1882. Allen Wright died in 1885 and was buried at his home in Boggy Depot, Oklahoma.

-

Templeton, RichardRichard K. Templeton, Union Class of ’80, is the Chairman, President and Chief Executive Officer of Texas Instruments Incorporated (TI), a global Fortune 500 company with nearly $13 billion in revenue and about 32,000 employees. TI has a long-standing tradition of bringing innovative technologies to market. In the 1950s, TI engineers developed the first commercial silicon transistor and invented the integrated circuit. Today, its engineers continue to innovate with a portfolio of 100,000 semiconductors that are used in a myriad of electronics, from toothbrushes to tablets and from automobiles to appliances. TI is among the top semiconductor producers in the world. Templeton entered Union College in 1976 and graduated cum laude in 1980 with a B.S. degree in Electrical Engineering while also playing linebacker for the varsity football team. At Union, he met his future wife Mary (Haanen) Templeton who graduated in 1980 with a B.S. in Computer Science and is currently serving as a trustee of the college. Mary and Rich have three children: Stephanie (25), John (23) and Jim (22). In an era when many professionals frequently change fields and employers, Templeton has spent his entire career at TI, beginning a week after graduation in an entry-level engineering position and working his way up to president and CEO in 2004 and chairman in 2008. Understanding that analog semiconductors are essential in our increasingly digital world, Templeton has led TI to become the global leader in analog integrated circuits, while still maintaining the company’s strengths in embedded systems and digital signal processing. Under his direction, the value of TI’s stock has grown 70 percent and dividends to shareholders have increased by a factor of 14. He has been singled out as the semiconductor world’s best CEO multiple times by financial analysts and portfolio managers who follow the industry. But Templeton’s leadership has not only benefited investors: TI has been ranked as one of the top companies in employee happiness, showing that business success and employee satisfaction can grow together. Through his actions, Templeton has shown he also understands that success is measured by more than a profit statement and he has set the tone at TI by personally leading its United Way campaign for many years, resulting in tens of millions of dollars of donations to a variety of charitable organizations. Reaching out beyond the walls of TI, he has also chaired the Metropolitan Dallas United Way campaign, leading it to a record fund-raising year in 2012. Together with his wife, Mary, Templeton has established a charitable foundation that has donated millions of dollars to educational and arts organizations. Templeton has also given his time and energy to the advancement of technological innovation and education, particularly STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education. He personally led North Texas CEOs in a “STEM in the Schoolyard” project with fifth graders at a Dallas elementary school. Under Templeton’s leadership, the company and the TI Foundation have invested $150 million over the last five years to strengthen global education programs including K-12 STEM teaching and student achievement. In the U.S., these efforts are especially directed toward increasing skills among under-resourced communities and under-represented minority students and girls. The industry has taken note of Templeton’s commitment and passion in this area. In 2012, he received the Semiconductor Industry Association’s highest award, citing his service as a “vigorous advocate for STEM education and longtime champion of research and innovation.” Through his business success, his leadership by example and his giving of his time and resources to the community, Richard Templeton has lived the creed of a Union College Liberal Arts education: Think, Connect, Act.

-

Stone, NikkiOlympic gold-medalist Nikki Stone was born in Princeton, New Jersey on February 4, 1971. She graduated Magna Cum Laude from Union College in 1995, and has a Master’s degree from the University of Utah in Sports Psychology. Stone is a former Olympic aerial skier. Aerial skiing involves skiing at about forty miles-an-hour into a ten-foot snow jump, flipping and twisting at a height of approximately fifty feet, and then landing and skiing to the bottom of a steep hill. Nikki competed in the 1998 Olympic Games in Nagano, Japan and was the first American to win a gold medal in her sport. In her career, she has won thirty-five World Cup medals, eleven World Cup titles, four national titles, two year-long Aerial World Cup titles, and a World Championship. She was also the first pure aerialist ever to become the year-long Overall Freestyle World Cup Champion. In 2003, she was inducted into the National Ski Hall of Fame. What is especially impressive about Stone’s victory is that 18 months before her Nagano appearance, she suffered a career-threatening spinal injury and doctors said she would never walk again. Years of repetitive impact had taken their toll on Nicki’s back, and two of the discs were seriously injured. Each of the ten doctors Stone visited told her she would no longer be able to ski. The months that followed were hard on her and she went into a deep depression. Nikki found inspiration in a poem by an unknown author titled You Must Not Quit, as well as in the story of Joe Frazier, who won an Olympic gold medal in boxing in 1964 with a broken thumb. “If he could win boxing with a broken fist, I could win skiing with an injured back” she said. Finding a doctor who would work with her was not easy, but Stone found one who encouraged her to strengthen her back muscles in the hope that they might support the injured discs. Although a risky process due to the fragility of her disks, Stone wanted to try. She trained through the pain, not knowing if she would go too far, because there was such a delicate balance between strengthening the muscles to protect the damaged discs and causing further injury. Gradually, she began training to compete again, with an eye on the World Championship several months away. “I had to dig deep to build my own confidence,” Stone says. And although she performed poorly during the competition, with members of the media predicting she would never stand on a winner's podium again, Stone was pleased she had gotten so far. “Although it didn't happen overnight, I realized that everything from that point forward was a bonus.” After all, doctors had told her she would never jump again and she was jumping. With less than a year to train for the next Olympic Games, Stone “stuck her neck out” and pushed toward her goal. She trained with intensity, consistently improving her strength, agility, and confidence, winning the 1998 gold medal for aerial skiing. In January 2010, Stone released her book When Turtles Fly: Secrets of Successful People Who Know How to Stick Their Necks Out. Her book intertwines her own story with those from other contributors, such as Shaun White, Tommy Hilfiger, Lindsey Vonn, Dr. Stephen Covey, and Prince Albert. She is also a contributor to Awaken the Olympian Within: Stories from America's Greatest Olympic Motivators (1999). Currently, Stone is a motivational speaker, author, and a motivational coach for the new regional The Biggest Loser program in Wichita, Kansas. She has worked as a visiting professor at the University of Utah and a sports psychology consultant for several elite and Olympic athletics.

-

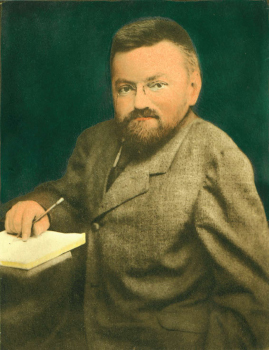

Steinmetz, Charles ProteusElectrical engineer, inventor, and educator, Charles Proteus Steinmetz was born Carl August Steinmetz in Breslau, Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland) in 1865. In 1883 Steinmetz enrolled at the University of Breslau to study mathematics. True to his philosophy of education, he pursued an unusually broad course of studies, including astronomy, biology, chemistry, electricity, physics, and political economy. Steinmetz was also attracted to socialism, leaning toward the tenets of that doctrine that emphasized peaceful change and the foundation of cooperative communities. “Cooperation” became the central theme of a lifelong intellectual quest for the ideal political system. Steinmetz fled Germany in 1888 when he came under police suspicion for editing a socialist newspaper at a time when socialism was illegal. He arrived in New York City in 1889, speaking no English, with $10 in his pocket and no job. He soon found work in New York City and there made his first major contribution to electrical engineering, developing the law of hysteresis. Eventually employed by the General Electric Company in 1892, and relocating to Schenectady in 1894, Steinmetz remained with General Electric until his death in 1923. Early in his career Steinmetz made two other major contributions to electrical engineering: the application of imaginary number calculations to the solution of electrical engineering problems, and the theory of transient phenomena and oscillations. Awarded honorary degrees by both Harvard University and Union College, Steinmetz was for two generations, a_er Edison, the most recognized name in the realm of electricity. He became Professor of Electrical Engineering at Union College in 1902, as well as Chairman of the Electrical Engineering Department in 1905. After World War I, Steinmetz ceased lecturing at Union College, though he remained a nominal member of the faculty and a warm and active friend of the College for the remainder of his life. Steinmetz wrote that “Teaching is the most important profession, because upon teachers depends the future of our nation, and, in fact, all civilization.” Steinmetz was unusually short in stature and suffered from kyphosis, an abnormal curvature of the spine, both of which he inherited from his father. Although this restricted his physical activity, it did not prevent him from enjoying canoeing, swimming, biking, and other outdoor pursuits, which he loved and engaged in throughout his life. He was also an avid photographer, with a great love of trick photography. He experimented with multiple exposures and layered negatives, creating images, for example, in which he contrived to be present multiple times. In addition to publishing numerous technical papers, lectures, and books, Steinmetz interpreted Einstein’s ideas to the public, spoke favorably of the prospects for extraterrestrial life, ran strongly but unsuccessfully for New York State Engineer on the Socialist ticket, and started the Steinmetz Electric Car Company in 1917. He continued an active schedule of lecturing throughout his life. Following an exhausting lecture tour to the west coast, Steinmetz became ill suddenly, and died at home in Schenectady on October 26, 1923.

-

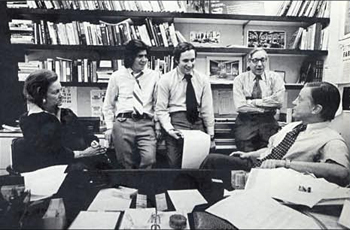

Simons, Howard"A newspaper in this country ... should be free to publish whatever it learns, limited only by the application of its own standards of taste and fairness; the application of a standard that it will not knowingly publish false information; and, finally, that what it publishes will not clearly endanger a human life" - Howard Simons, Union College, June 16, 1973. Howard Simons, one of the country's leading newspapermen, was Managing Editor of The Washington Post from 1971 to 1984, and a key figure in its Watergate investigation. Although he is most remembered for giving Woodward and Bernstein's secret informant the name "Deep Throat" (after the notorious 1970s porn movie), his less-well-known behind-the-scenes role in Watergate was central to the investigation. Working closely with editor Bill Bradlee and publisher Katharine Graham, Simons was a key figure in assigning Woodward and Bernstein to the Watergate story, keeping them on it, and backing their efforts when much of official Washington was trying to ridicule the investigation and many at the Post were skeptical. According to the two cub reporters, he was "the day-to-day agitator, the one who ran around the newsroom inspiring, shouting, directing, insisting that we not abandon our investigation." Without Howard Simons' persistence and journalistic integrity, the Watergate investigation might well have gone nowhere. Simons, who grew up in Albany, worked his way through Union College, receiving a B.A. in 1951; the College honored him with a D.Litt. in 1973. At Union, he was an English major with a strong interest in history, President of the Senior Class, Editor of the Idol, a member of the Mountebanks, a member of the Union College Publications Board, and College Reporter for the Schenectady Gazette. From Union, he went to the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, receiving an M.S. in 1952. He worked in Army Intelligence, and in 1954 became a reporter and later News Editor for the D.C.-based Science Service. He was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard in 1958-59. He moved to The Washington Post as a science writer in 1961, receiving several prestigious awards for his science reporting - and much notoriety for his investigative series about the loss of an H-bomb off Spain. Bradlee tapped him for an administrative post in 1966, and he became Managing Editor in 1971, supervising 500 people. After a distinguished career at the Post, he became head of the prestigious Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University in 1984 where he remained until his death from cancer at the age of 60 in 1989. He returned to Union to give the Commencement Address in 1973, entitled, "The Founding Fathers, the Free Press and the Republic: Don't Shred on Me"; he returned again to Union in 1985 to give a Minerva lecture entitled, "The Freer the Press, the Freer the Society." Underneath a tough persona, he was a man of much sensitivity and compassion who championed the underdog. He supported native American efforts in journalism, he organized a fund in support of UNICEF, and he helped establish a fellowship program for Third World journalists at the Columbia School of Journalism. A prolific writer, Simons was the author of Jewish Times, an oral history of the American Jewish experience, and of Simons' List Book, a reference work of great use to journalists. He also co-edited The Media and Business and The Media and the Law, and together with Haynes Johnson, wrote a spy-thriller, The Landing about the Nazi insertion of spies on Long Island during World War II. He was a man of enthusiasm, energy, and drive, a skeptical reporter with a sharp wit and a healthy sense of the irreverent. The Post called him a person with a "restless intellect and an urge to teach" who developed talent and encouraged young people of all kinds. He was a life-long campaigner against deception, a champion of journalistic integrity, and a crusader for freedom of the press.

-

Seward, William HenryBorn in 1801, Seward graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Union College in 1820, where he impressed classmates with his “remarkable assiduity and capacity of acquirements.” Admitted to the bar in 1822, he later entered politics as an anti-Masonic State Senator, and then served two terms as Governor of New York as a Whig (1839-1843). Among his many proposals for social reforms were better treatment of prisoners, the insane, debtors, and immigrants. He gained a reputation in some quarters as a radical for championing a law encouraging rescue of free African Americans kidnapped into slavery. Seward earned the everlasting enmity of nativists by his support of immigration and equal educational opportunity for Irish Catholic children. Seward was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1849 and 1855. Shortly after Seward’s election in 1849, Union College President Eliphalet Nott wrote, urging the new Senator to continue “advocacy of liberal principle without distinction of caste or color” and to stake his future on adherence to those principles. Although he had built a reputation as a passionate opponent of slavery, his commitment to preserving the Union put him in opposition to radical abolitionists, including those in Congress. Seward’s “Higher Law Speech” (1850) and his “Irrepressible Conflict Speech” (1858) provoked angry attacks from Southern Senators. After the first speech, Nott wrote that “I am glad to see that you do not lose your temper, that you do not return railing for railing, but that no array of talent, no manifestation of rage deters you from speaking and acting as a freeman ought to speak and act everywhere and in the face of all men.” Partly because of the opposition of nativists, Seward lost the Republican nomination for President to Abraham Lincoln in 1860. As Lincoln’s Secretary of State he gradually became the president’s closest confidante and social companion. Seward came to see that he and Lincoln had much in common: adherence to principle tempered by pragmatism, a deep commitment to saving the Union, principled opposition to slavery, and a taste for story-telling. Seward’s greatest accomplishment as Secretary of State consisted of the complex diplomacy that kept Great Britain and France from recognizing and assisting the Confederacy. Seward continued as Secretary of State under Andrew Johnson and negotiated the purchase of Alaska. Although Seward is generally considered one of the greatest secretaries of state in American history, his later years in the office were personally harrowing. He was badly injured in a carriage accident in 1865. Soon afterward, on the same night that John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln, Seward and his son Frederick, were each gravely wounded by a knife-wielding Lewis Powell, one of Booth’s conspirators. Two months later Seward's wife died, and their only daughter, Fanny, his favorite child, died a year later. Seward commented ruefully in 1867 or 1868, "I have always felt that Providence dealt hardly with me in not letting me die with Mr. Lincoln. My work was done, and I think I deserved some of the reward of dying there." William Henry Seward died at his home in Auburn, New York, on October 10, 1872.

-

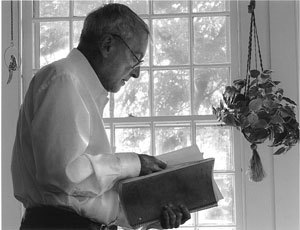

Selzer, Richard“Blood and ink, in my hands, have a certain similarity,” Richard Selzer ’48 once wrote. “When you hold a scalpel, blood is shed; when you hold a pen, ink is spilled. Something is let in each of these acts.” Selzer, whose writing describes the responsibilities, rewards and challenges of being a surgeon, is a pivotal figure in medical humanities. More widely, he has helped define our culture’s evolving sense of medicine and healthcare. From an early age, Selzer cultivated interests in both medicine and literature. Born to Russian immigrants in 1928 in Troy, N.Y., Selzer was the son of a family physician who brought him on rounds and instilled in him a love of the human body and what Selzer later called “the glorious privilege of healing it.” At the same time, his mother – an artist, singer and actress – fueled his passion for literature by immersing him in Russian fairy tales, Greek mythology and Aesop’s Fables. When Julius Selzer died suddenly of a heart attack, the 13-year-old vowed to fulfill his father’s dream and pursue a career in medicine. His mother’s influence remained, however, and his passion for literature would blossom decades later. At Union, Selzer majored in biology but took a steady dose of courses in French, psychology, English literature and composition, and European history. “This diverse undergraduate experience, merging the two seemingly disparate fields of science and the humanities, was fundamental to his hybrid artistry,” wrote Mahala Yates Stripling, author of Imagine a Man: the Surgeon Storyteller, a literary biography of Selzer. Leonard Clark and Allan Scott who were biology professors known for their wide-ranging research interests inspired Selzer while he was at Union. He was a member of Phi Sigma Delta fraternity and wrote for the student newspaper, Concordiensis. He recalled his time at Union as “an intimate, personal, thorough education at a small, congenial college.” After Union, he went on to Albany Medical College, earning his M.D. degree in 1953. He served a surgical residency at Yale University, interrupted by two years of service as an Army medic during the Korean War. In 1960, he began a private surgical practice at Yale-New Haven Hospital. At 40, he began to write by instituting a dedicated routine of going to bed early and getting up in the middle of the night to write. Selzer prefers to write in longhand, as if holding a scalpel. A mystery magazine published his first stories. His first book, Rituals of Surgery, a collection of short stories, was published in 1973 followed by Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery (1976), Confessions of a Knife (1979), and Letters to a Young Doctor (1982). These works sparked the literature-and-medicine movement that has become important to a new doctor patient-centered medicine, according to Stripling. Today, his work – rich in themes of empathy in the doctor-patient relationship – is integral to the canon of literature used to train humanistic doctors. Selzer, who holds an honorary doctor of science degree from Union, retired from medicine in 1985 to write full-time. Books by Richard Selzer ’48: Rituals of Surgery (1973); Mortal Lessons: Notes on the Art of Surgery (1976); Confessions of a Knife (1979); Letters to a Young Doctor (1982); Taking the World in for Repairs (1986); Imagine a Woman (1990); Down from Troy: A Doctor Comes of Age (1992; autobiography); Raising the Dead: A Doctor’s Encounter with His Own Mortality (1993); What One Man Said to Another: Talks with Richard Selzer (1994; with Peter Josyph); The Doctor Stories (1998); The Exact Location of the Soul: New and Selected Essays (2001); The Whistler's Room: Stories and Essays (2004); Knife Song Korea: A novel (2009); Letters to a Best Friend (2009; with Peter Josyph); and Diary (2010)

-

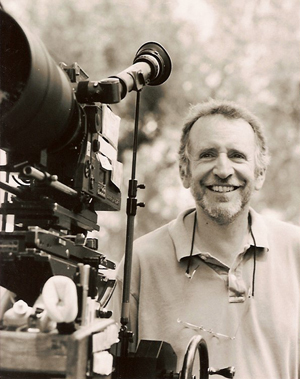

Robinson, Phil AldenPhil Alden Robinson graduated from Union College in 1971 with a major in Political Science. In a sense, he launched his career with the completion of his senior project, a documentary on “The New Deal Coalition” under the supervision of the late Joseph Board, the Robert Porter Patterson Professor of Government. Refusing to be pigeon-holed, Robinson has written and/or directed feature films as different as In the Mood (1987), Field of Dreams (1989), Sum of All Fears (2002), and Sneakers (1992). One of these films, Field of Dreams, has achieved mythic status as perhaps the best baseball film ever made. About memory, about failing to achieve one’s dreams, about coming to terms with one’s past and one’s present and, not least, about the magical hold that the beauty of a baseball field has on the American heart and mind, Field of Dreams was nominated for three Academy Awards, including one for “Best Screenplay Adaptation,” a Directors Guild of America award, and a Writers Guild of America Award. It also won Premiere Magazine’s poll for best picture of 1989. Thousands of people have visited the Iowa site of the film, proving it would seem, that “if you build it they will come,” even though the actual line spoken in the film is, “If you build it he will come.” “Dream Fields” have popped up all over the United States, including a giant complex outside Cooperstown at which thousands of young players from all parts of the nation have played during summer tournaments. A commitment to truth and to giving witness to the painful realities of violence in the contemporary world underlie some of Robinson’s most impressive work. As an observer he accompanied the United Nations High Commission for Refugees on humanitarian visits to Bosnia and Somalia, visits that exposed members and observers to danger. This led him to produce five powerful documentaries on the terrible conditions in those countries. Robinson’s documentaries were aired on ABC’s “Nightline,” and Sarajevo Spring was nominated for an Emmy Award in the category of “National News and Documentary.” He regards these documentaries as his proudest achievement. Concerned that the media often presents a distorted picture of the civil rights struggle in Mississippi, Robinson produced a made-for-TV movie, Freedom Song, that in part attempted to “set the record straight” by looking at the grass roots struggle in its human dimensions. The film won a Golden Gate Award at the San Francisco Film Festival (2001) and a Writers Guild of America Award. It was also nominated for two Emmy Awards, a Screen Actors Guild Award and several other awards, among them three NAACP Image Awards. Perhaps Robinson’s most acclaimed work was part of a joint project with a number of other directors. He directed the first segment of HBO’s Band of Brothers, a series that won an Emmy and a Golden Globe (2002). Always active in advancing his profession and community, in 1994 Robinson received the Writers Guild Valentine Davies Award for “contributions to the entertainment industry and the community at large.” The most notable feature of the work of Phil Alden Robinson is that it has achieved distinction in a variety of forms and in two very different endeavors. He has excelled as a director and a screenwriter, and he has produced award-winning work in three distinct genres, the feature film, the made-for-TV movie, and the documentary. Few indeed can match his record.

-

Raymond, Andrew Van VrankenMany argue that Andrew Van Vranken Raymond saved Union College from extinction. One of the College's most important and effective leaders, Raymond (1854-1918), Class of 1875, was the last Union alumnus to become President of the College, serving from 1894 until 1907. Inheriting an institution whose alumni were torn apart by a thirty-year-long factional war, whose student body was shrinking, whose annual deficits were life-threatening, and whose faculty were demoralized both by low compensation and by attempts to close the campus and move its remains to Albany, President Raymond proceeded with energy and diplomacy to engage these problems, and he passed on to his successor an institution with sound finances, a revivified faculty, a vastly improved physical plant, and solid prospects for a brighter future. Moreover, despite the critical situation of the College when he took office, Raymond had to overcome a great deal of debilitating opposition from the Board of Trustees to accomplish his needed objectives. Raymond has been described as a hearty and good-natured man with a "magnetic" personality and a statesmanlike temperament. He was an inspiring speaker. At Union, he had been an excellent athlete who had hit a record-setting grand slam home run from a home plate near North College that bounced off the South Colonnade over 500 feet away. He also held for a while an Adirondack League Club fly-fishing record. Most importantly for Union, Raymond had a strong sense of priorities and the patience and persuasive power to convince others to support those priorities. Upon arrival, he hired a new administrative team, rationalized cash flows, and recruited impressive new faculty. After much argument, he convinced the Trustees to sell College property on Long Island and east and west of the Schenectady campus to raise the funds needed to retire debt, establish an endowment, and stabilize finances. He persuaded the legendary Frank Bailey (Class of 1885) to become Treasurer in 1901, a major development in Union's financial history. Fighting on behalf of faculty compensation, Raymond nevertheless presided over austerity conditions for most of his term in office (taking cuts in his own salary), but he was still able to institute a policy of sabbatical leaves for faculty. Arguing that "the appeal of progress is always stronger than the appeal of dire need" when it came to raising money, he promoted a vision of enhanced instructional and physical resources for the College. One of his greatest accomplishments was to build a major Electrical Engineering Department, convincing Charles Steinmetz to lead it and General Electric to build a home for it. He convinced Andrew Carnegie to donate $100,000 for a General Engineering Building (currently the south half of Reamer Hall), and agreed to raise an equal amount, largely from the alumni, to add to the endowment. Carnegie also gave Raymond enough money to convert the Nott Memorial into a significant library space. Silliman Hall was built during his administration to house student organizations, and there was extensive dormitory renovation. In addition, three attractive fraternity houses were built (Alpha Delta Phi, Kappa Alpha and Sigma Phi). With these developments, the student body began to grow, reversing a quarter-century of decline, and the first significant admission of Jewish students to Union College began during Raymond's administration. Raymond had a strong commitment to memorializing the College's history, presiding over its centennial celebration, initiating Charter Day (now Founders' Day), and writing/editing a somewhat fulsome three-volume history-with-biography of the College and its significant role-players. He resigned from the presidency in 1907 to accept a pastorate in Buffalo at twice his Union College salary. He remained active in higher education after his retirement from Union, and a Chair in Classics at the University of Buffalo is named for him.

-

Ramée, JosephWhen French architect Joseph Ramée first arrived in Schenectady in January of 1813, there was little to suggest that the small rise a half mile east of town would become a campus, much less one of the most innovative, recognized and influential campuses in America. Ramée arrived in Schenectady thanks to David Parish, a Belgian financier who had brought the architect to America to design an estate on Parish’s land along the St. Lawrence River. When economics thwarted Parish’s dream, the banker brought Ramée and his family to Philadelphia to find him work. The cold and snowy trip, largely by sleigh, included a stop in Schenectady where Parish introduced the architect to a young and energetic college president, Eliphalet Nott, who was set to launch the ambitious expansion of a college not yet two decades old. Before he met Ramée, Nott had envisioned a long row of buildings, similar to the Yale row that was copied at a number of institutions. But it was Ramée who helped make the campus a distinctly new college model for post-Revolutionary America: a broad courtyard with facing mirror-like buildings north and south connected by arcades to a building at the east end and a large round building at the center. Symbolically, the campus is open toward the expanding western frontier. On the periphery, informal landscaped grounds echo the style of European parks and gardens. Born along the Belgian-French border in 1764, Ramée trained in Paris, where he developed a taste for the elegant and clean neoclassicism that would define his career. He did important work in Paris, designing a number of townhouses, before he joined the revolutionary army. After being caught up in a plot against the government, he had to flee in 1793. He practiced briefly in Belgium but French military advances in 1794 drove him to Germany, where he designed estates for Saxon dukes from his base in Hamburg. In 1805, he married Caroline Dreyer, and a year later they had their only child, Daniel. Turmoil in Germany and Denmark forced another move back to Paris in 1810. Besides his work for Union, he designed homes and estates in Philadelphia, Baltimore and New York State. During his four years in America, he made unsuccessful entries in design competitions for both the Washington Monument in Baltimore and the Baltimore Exchange. He returned to France in 1816 after the fall of Napoleon, and spent the rest of his career working in Belgium, Germany and France. In the last decades of his life, he produced publications of his designs that today are extremely rare. For example, there are only two known copies of Parcs et jardins, one of which is in Schaffer Library’s Special Collections. We are indebted to Paul V. Turner ’62, the Paul L. and Phyllis Wattis Professor of Art Emeritus at Stanford University, for his contributions to our knowledge of Ramée and the Union College campus. Prof. Turner is the author of two books, Joseph Ramée: International Architect of the Revolutionary Era (1996, Cambridge University Press) and Campus: An American Planning Tradition (1984, The Architectural History Foundation/MIT Press.)

-

Potter, Edward TuckermanArchitect Edward Tuckerman Potter's work literally stands front and center at Union College: he designed the Nott Memorial, the President's House and the Feigenbaum Administration Building, as well as the Mark Twain House in Hartford, CT and several churches now on the National Register of Historic Places. Potter, born in Schenectady on September 25, 1831, was the fourth son of Union professor Alonzo Potter and Sarah Maria Nott, the only daughter of Union's fourth president, Eliphalet Nott. Edward began his collegiate studies at the University of Pennsylvania before transferring to Union in 1851 as a junior. Following his graduation in 1853 he apprenticed with New York City architect Richard Upjohn before opening his own New York offices in 1856. That same year Potter accepted his first independent commission, to design the President's House at Union. In 1858, Potter was assigned the daunting task of designing the building known today as the Nott Memorial, originally called Alumni or Graduates' Hall. While the foundations for the building were laid just a year later, a shortage of funds prevented additional work until the early 1870s. Following his grandfather's death in 1866, Potter thoroughly revised Ramée's original plans for the central domed rotunda, ultimately resulting in the unique edifice that is the Nott Memorial. Potter's major buildings are known for their use of multi-colored stone, polished granite columns, elaborately carved decorations, and for distinctive motifs, including five- and six-pointed stars as well as a pentagonal ivy design, all of which can be seen in the Nott Memorial. There is, some scholars argue, much symbolic import in Potter's choice of these particular design elements. While perhaps best known for the Nott and the Mark Twain House (1873), the vast majority of Potter's architectural plans were for churches: of the seventy-nine buildings he is known to have designed, at least sixty-six were churches, and of those forty-two still stand. They include St. John's Episcopal Church in East Hartford, CT, All Saints' Memorial Church in Providence, RI, and Trinity Church in Wethersfield, CT. He also designed the President's House and Packer Hall university center at Lehigh University. A 1902 University of Pennsylvania publication describes Potter's style as “distinguished by its freshness and originality of conception, felicity of ornamentation and delicacy of feeling.” Edward Tuckerman Potter's family connections to Union ran deep: not only was his father an alumnus and a professor and his grandfather the College's longtime president, but his younger brother Eliphalet Nott Potter (Class of 1861) also served as president from 1871 through 1884. His brothers Clarkson Nott Potter (Class of 1842), Howard Potter (Class of 1846) and Robert Brown Potter (Class of 1849) were all deeply involved with Union in various capacities: it was, in fact, large donations from Clarkson and Howard Potter which made the completion of the Nott Memorial possible. Potter retired from architectural work in 1877, and died on December 21, 1904. An obituary in The American Architect reports that Potter, “possessing independent means,” was able to retire early and devote himself to “travel, the study of music and philanthropy.” Potter worked in his later years to devise “ways and means of securing to tenement houses and their inmates not only economical and convenient planning, but the best of natural ventilation and lighting.… In all tenement and prison reform movements he took an active part, so that, quite apart from his architectural work, he led a satisfying and useful life, to which further grace was added by his musical successes as a composer of sacred and even operatic scores.”

-

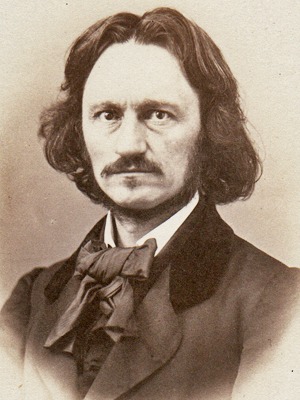

Peissner, EliasPeissner was born in Vilseck, Bavaria in 1825. He enrolled at the University of Munich in 1843, studying philosophy and law, but was forced to leave the university shortly before graduating through an intriguing turn of events. In 1846, actress and dancer Lola Montez became the mistress of King Ludwig I. Montez also dallied with university students, including Peissner, then president of his fraternity. Her meddling in political affairs made her unpopular with the students, and Peissner’s connection with her led to his being expelled from the fraternity. Peissner then founded a new fraternity, Allemannia, which supported the King, creating political tension between the new fraternity and the existing ones. Ludwig intervened on the side of Montez and Peissner, leading to rumors that Peissner was the illegitimate son of the King, a rumor supported by the strong physical resemblance between them. When the revolutions of 1848 struck Munich, the majority of students took the republican side, but Peissner and his fraternity rallied to the King. Peissner was expelled from the university, and Ludwig briefly ordered the university closed in February, but Ludwig abdicated in March, and Peissner was forced to leave Bavaria. He accompanied Montez to Switzerland, but she later moved to London and left him behind. Although Ludwig corresponded with Peissner and gave him money for his education, Peissner decided to start over again in the United States. Working as a tutor, Peissner met Professor Charles Foster of Union College, who arranged his appointment as instructor of German and Latin in 1850.He also taught fencing. In 1855 he was appointed Professor of German Language and Literature, despite anti-Catholic sentiment at the college, and in 1857 became Lecturer in Political Economy, the forerunner of today’s economics discipline. He was elected to Phi Beta Kappa and also joined Sigma Phi. He married Margaret Lewis, daughter of Professor Tayler Lewis, in 1856; they had three children. He wrote grammars of German and the Romance languages and a history of German literature. He also became involved in politics, calling for the North to resist Southern secession his 1861 book, The American Question. When the Civil War broke out that year, Peissner helped organize and train the Union College Zouaves, most of whose members later served as officers in the Union Army. In June 1862, Governor Morgan of New York gave Peissner permission to recruit a regiment and a commission as its colonel. The regiment entered service that September as the 119th New York Infantry. The regiment saw its first action in 1863 as part of XI Corps at the battle of Chancellorsville. The corps’ position was turned by Stonewall Jackson’s attack, and disaster ensued. Desperately attempting to stem the Confederate tide, Peissner was shot at the head of his men, and died on the field on May 2, 1863. On his death, the faculty at Union College formally expressed their, “respect for his ability and earnestness in his department, both as an Author and an Educator,….regard for his virtues as a man and a friend,….[and] admiration of his heroism in the cause of human liberty and his adopted land.”

-

Payne, John HowardOn the main entrance gate to Union College sits a bronze tablet inscribed with the words, "To the memory of John Howard Payne, the author of Home Sweet Home, a student of Union College in the class of 1810." The gate was dedicated at the 1911 Commencement at which time the Metropolitan Opera soprano Alma Gluck sang "Home, Sweet Home." In 1913, all four verses of the poem were added to the gate's center pillar. Union's inscription correctly notes that John Howard Payne is the author of the text and not the composer of the music. In fact, the melody was written by Henry Bishop and may have been based on a Sicilian folk tune. At its first appearance in the 1823 Covent Garden operetta, Clari; or the Maid of Milan, the song made Payne a famous man. John Howard Payne was born in New York City in 1791 and spent much time at his grandfather's house in East Hampton - now the Home Sweet Home Museum. His dramatic talent was evident from an early age. As a 14-year-old he published The Thespian Mirror, a journal of theater criticism, and soon after he wrote his first play, Julia, produced at the Park Theater in New York. A wealthy benefactor, John E. Seaman, underwrote Payne's education at Union College from July 1806 to November 1808 during which period Payne published twenty-five issues of a periodical called The Pastime. However, when Payne's mother died and his father's business failed, Payne returned to the Park Theater and made his triumphal first appearance as a professional actor as "Young Norval," hero of John Home's Tragedy of Douglas. In 1813, Payne sailed to London, the first American actor to invade the English stage, and for the next twenty years he pursued a flamboyant career in Europe as actor, playwright, and producer. He spent time in debtor's prison, was rumored to have been enamored of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and he was a friend of Washington Irving and collaborated with him in the 1824 play, Charles the Second - produced at Union College by the Mountebanks in 1936 and again for the Bicentennial Celebrations in 1994. Payne returned to the United States in 1832 where his career took two remarkable turns. He was sympathetic to the plight of the Cherokees in Georgia and lobbied Congress to try to prevent the Cherokees from being forced from their ancestral home (for which the Georgia Guard held him captive for a few weeks in 1835). Later, he was appointed U.S. Consul at Tunis in 1842-43, and again from 1851 until 1852, the year of his death. Meanwhile, "Home, Sweet Home" continued to grow in popularity, being widely sung during the American Civil War. When celebrated soprano Adalina Patti sang at the White House in 1862, President Lincoln asked her to perform the song for which John Howard Payne is most remembered. In 1883, Payne's ashes were brought back to the U.S. from Tunis and re-interred in Washington, DC. At the grand memorial service held in Oak Hill Cemetery, attended by President Chester Arthur, a full choir sang "Home, Sweet Home." "'Mid pleasures and palaces though we may roam, Be it ever so humble, there's no place like home."

-

Patterson, Robert PorterIt is not an exaggeration to say that Robert Porter Patterson was among the most important people responsible for shaping the allied victory in World War II, although his extraordinary modesty never permitted him to claim credit for it. As Under Secretary of War from 1940-1945, he was the person most responsible for mobilizing and organizing America's industrial resources to produce the weapons and equipment with which the war was eventually won by the United States and its allies. When he took office in 1940, America was largely an unarmed country; by the end of the war in 1945, it was producing a greater supply of military goods than were being produced by its enemies and allies combined. Roosevelt had famously promised that America would become the Arsenal of Democracy; it was Patterson, more than anyone else, who presided over the creation of that arsenal. Born in Glens Falls, NY, Patterson graduated from Union College in 1912 and from Harvard Law School in 1916. A combat veteran of World War I, he fought (among other places) in the furious battle of the Argonne Forest, and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and the Silver Star for bravery. Returning to civilian life, he worked for a decade as a Manhattan attorney until being appointed Judge of the US District Court in Manhattan by President Hoover in 1930. A Republican with reservations about much New Deal legislation, he nevertheless upheld from the bench Congress' right to fight the depression by enacting such legislation. In 1939, Franklin Roosevelt appointed him to the Federal Court of Appeals in New York. As Hitler marched across Europe, Judge Patterson resigned from the Appeals Court and enlisted in the Army, looking once again to share the challenges of combat. Literally while on KP duty in boot camp, he was summoned to Washington by President Roosevelt to fill the high position he was to occupy in the outer cabinet for the duration of the war, serving with John McCloy and Robert Lovett under the legendary Henry Stimson, who was Hoover's Secretary of State and Roosevelt's longest-serving Secretary of War. In this capacity, Patterson was to be in charge of military procurement, constantly in contact with hundreds of managers in America's industrial world, awarding billions of dollars worth of military contracts without a hint of scandal, as America converted the old factories and built the new factories needed to achieve the massive wartime production on which victory in World War II depended. When Stimson retired at the end of the War, President Truman appointed Patterson to succeed him as Secretary of War (having also offered Patterson an appointment to the Supreme Court). In this post, Patterson presided over the demobilization of a large percentage of the armed forces he had helped build during the War, but also over the reconfiguration of the remaining armed forces to fulfill the evolving missions of the newly-emerging Cold War. Together with George Marshall, Patterson was the principal architect of the new Department of Defense, created in 1946. He was asked to serve as the first Secretary of Defense, but decided instead to return to civilian life. He became a prominent New York attorney, but was tragically killed in a airplane crash in Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1952. In his memory, family and friends established the Robert Porter Patterson Professorship in Government at Union College. One of the "Wise Men" of that generation, good citizenship, rectitude, honesty, and energy characterized his personal and professional values, as attested to by the New York Times editorial on the occasion of his death: "Here was a man of superlatively high standards, complete integrity, and boundless enthusiasm for whatever task he took in hand. No one ... is likely to forget the candor of his speech, the courage of his faith, the warm and glowing brightness of his friendship. ... He fought hard for every cause in which he enlisted, and the causes for which he fought were good and right." - January 23, 1952.

-

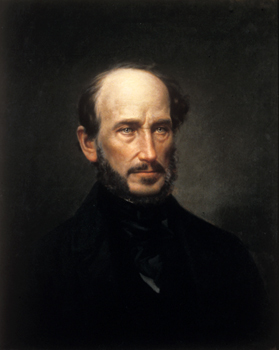

Nott, EliphaletIt has been said that Eliphalet Nott was a giant in his time. Quite aside from serving as the President of Union College from 1804 to 1866, he was also an entrepreneur, teacher, minister, scholar, inventor, and a powerful influence on American higher education in the 19th century. His students and protégés graduated to become leaders and founders of both public and private colleges and universities: Bowdoin, Colgate, Franklin & Marshall, Smith, University of Illinois, University of Iowa, University of Michigan, University of Pennsylvania, University of Rochester, University of the South, and William & Mary,to name only a few. The famous group painting, Men of Progress, executed by Christian Schuessele in 1862, featured Nott in the front center of the composition (which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery). In 1804, Nott was invited to assume control of a college short on space and without adequate funding. He was quickly thrust into the tangled world of New York state politics, out of which he emerged with a successful plan to help fund Union College with a state lottery. His vision was to make the college a match for, or superior to, other well-known institutions on the Atlantic Coast: Harvard, Yale, Rhode Island College (Brown), Queens (Rutgers), and Princeton (with which Union already had close ties). And for much of his presidency, he succeeded in that goal. But he also needed an entirely new location on which to construct his idea of a proper, unified college campus. So in 1807, Nott purchased some 250 acres on the slope where the College now stands. Nott had already begun the foundation of North College when in 1813 he met the noted French architect, Joseph Ramée. Their collaboration resulted in a milestone in the history of American collegiate architecture. Ramée’s master plan for Union was the most ambitious and innovative design for an American school up to that time and became a model for later campuses in both the North and South. Nott was willing to leave the ivory tower to participate in the growing technological and economic life of the nation. From 1829 to 1845 he served as president of Rensselaer Institute in Troy. His strong and enthusiastic interest in invention led him to pursue more efficient methods of home and industrial heating. Nott designed an eponymous stove that made use of cheaper and cleaner-burning anthracite coal, acquiring between 1832 and 1839 some thirty patents to protect his investment and corporate holdings. He also designed a steam-boiler system which he claimed to be more efficient than that of Fulton’s, and built a steamboat (the S.S. Novelty) to prove it. Nott’s most significant and far-reaching innovation in higher education was to promote the parity of classical and ‘practical’ education. By the second quarter of the 19th century, the traditional classical curriculum was gasping its last breath. It seemed clear that a Latin and Greek education, in all of its parts, was not adequate to the rapid changes occurring in the national and regional economy. A degree in engineering or chemistry, for example, seemed more likely to promote the general welfare than an intimate acquaintance with Homer and Ovid. Most of the engineers on the Erie Canal, sad to report, were mostly self-taught. In 1827, the College Board of Trustees authorized a parallel curriculum to permit students to choose between ancient and modern languages, and between abstract subjects and practical technology. This parallel curriculum was introduced in 1828 to support equally both spiritual America, as well as utilitarian America. All graduates alike were to receive the same A.B. degree. Civil engineering was introduced in 1845, and by 1857, Union could claim probably the best chemistry laboratory in America. By the time Nott died in 1866, he could, and would, be ranked among the half-dozen great college presidents of the 19th century.