Union At The Time

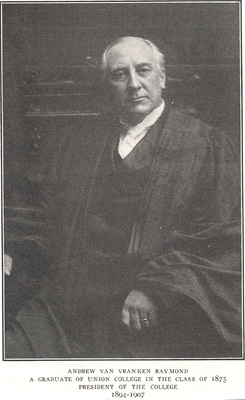

The decade during which Mrs. Perkins’ letters were written, 1895-1904, was a time of great challenge and change at Union College. The dates of her letters correspond closely with the term of office of Andrew Van Vranken Raymond (1894-1907), the ninth president of the College and one of the most influential in its history. The chief challenge that Raymond and the College faced during this period was a financial one, but the physical plant, faculty morale, enrollments, and the shape of the curriculum were also persistent concerns.

Union’s fortunes were indeed so dire when Raymond took office that it was on the brink of insolvency, and its shaky financial footing did not begin to turn around until 1901, when Frank Bailey, Union College Class of 1885, was asked by Raymond to become the College Treasurer. Bailey’s fiscal policies and leadership over the next 52 years and his personal donations to the College are largely credited with saving Union from financial ruin. His early efforts, however, were met with skepticism as well as hope on campus. As reported by Mrs. Perkins, Bailey’s appointment of the colorful C. B. Pond as his assistant treasurer and local enforcer caused particular resentment. While Pond did make sure that everyone paid their bills on time, many in the campus community, including Mrs. Perkins, objected to Pond’s confrontational style of conducting business. Also controversial was the decision during this period to sell off large plots of undeveloped land to the east and west of campus in order to settle College debts and improve its overall financial standing. Although effective, such strategies began the inexorable transformation of the Union campus from a largely open, wooded and pastured landscape into the more densely built property – closely bounded by residential areas – that it remains today.

Before this transformation began, however, Raymond’s administration was largely occupied by a proposal to move the College from Schenectady to Albany. The idea of moving Union to Albany in order to consolidate its location with that of the other members of Union University, including the Albany Medical College and the Albany Law School, had been considered before, but the attempt during Raymond’s administration was the most serious one. Contentious debate on this issue continued until mid 1896, when state funding for the move fell through.

The College faculty, which numbered about 25 in the decade of Mrs. Perkins’ letters, was directly affected by the fluctuating fortunes of the College. As the wife and mother-in-law of two Union professors, Mrs. Perkins reported that they sometimes went without pay or were uncertain about the security of their positions, as the College considered cutbacks in its staff to save money. At the same time, individual faculty members often taught a wide range of subjects or delivered lecture courses well outside their main areas of expertise. On the home front, the faculty formed a fairly close-knit community. Many faculty families, including the Perkins and the Hales, lived on campus, and widows or retirees were often granted a lifetime lease on their College homes. Nor was there a mandatory retirement age; several of Mrs. Perkins’ nearest neighbors were still teaching well into their eighties. Perhaps surprisingly, many faculty members and their families also found the means to travel widely. Back at Union, they socialized together frequently and appear to have derived particular pleasure from the twice-monthly meetings of the Schenectady Fortnightly Club, at which a member could address the group on any topic of interest whether related to an academic field or not.

Student life in the small Union community was also close-knit in more ways than one. Enrollments declined sharply in the years represented by the first half of the Perkins correspondence; between 1895-1896 and 1899-1900, the number of students at the College dropped from 252 to 182, or by almost 28%. But it grew gradually thereafter, and housing shortages became a persistent problem. There was simply not enough room to house all of the students in Union’s two dormitories, North College and South College, both of which had changed little from the time of their construction in the early nineteenth century. Like many of the faculty houses and classrooms on campus, the aging structures were poorly heated and lacked adequate facilities; although electric lights, steam heat, and improved bathrooms were installed in some sections at the turn of the century, a new dormitory providing additional rooms would not be built for decades.

The housing problem was addressed to some extent by the large-scale construction of fraternity houses during the period of the Perkins letters. Four capacious fraternity houses were built on campus during this decade, and it was often necessary for freshmen to move into fraternity houses at the beginning of their first term at Union because there was no room in the dormitories. Fraternities provided other types of bonds, of course, and Mrs. Perkins’ letters are full of their social activities and rivalries. Athletics was also a dominant interest for all at Union, with most competitive games being played on the center of campus in what is now Rugby Field. Mrs. Perkins had an excellent view of the games from her home in what is now Hale House, and she often reported their outcomes in her letters.

Changes to Union’s curriculum at this time were as fiercely debated as the move to Albany or the merits of different fraternities and football players. Financial retrenchment hampered some of Raymond’s efforts to strengthen the College’s scientific programs, but his initiatives in the area of electrical engineering took hold and resulted in the appointment of Charles Steinmetz to head a separate department in that field in 1902. Mrs. Perkins reported that some of the older professors, dedicated for years to the more classical curriculum, despaired at such innovations. Like the changes to the layout of the campus itself under Raymond’s leadership, they would leave a permanent mark on the kind of institution Union would become in the twentieth century.