Wild at Heart

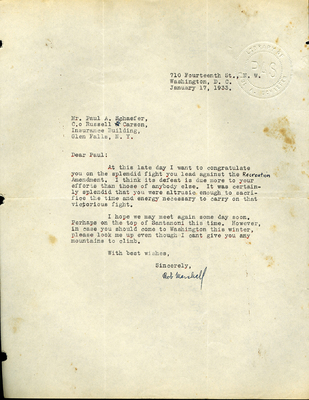

Paul Schaefer, a young, aspiring conservationist, was mentored by John Apperson Jr., a legend of the environmental movement. During the battle against New York’s Closed Cabin Amendment in the 1930s, Apperson quickly recognized Schaefer’s enthusiasm, patience, and innate ability to unite people in support of the cause. With these skills and invaluable guidance from both Apperson and Bob Marshall, founder of The Wilderness Society, Schaefer is now remembered as one of the key figures in the conservation movement.

Our entire system of government is founded upon the theory that the citizens of the State shall inform themselves accurately regarding the conduct of public affairs and if they do not approve of them, will take proper action to change their course. We are living not in an era of the divine right of kings but rather in one of referendum and recall.

-John S. Apperson Jr.1

To understand the story of Paul Schaefer, it is necessary to review the activities of his mentor, John Apperson Jr, around the time they met. By the 1930s, Apperson was firmly in his activist stride. In the 1920s his “weird genius of marked Machiavellian tendency, and unbounded perseverance and energy”2 became well known, and his achievements were impressive. In 1922, Apperson and Warwick Carpenter exposed presale timbering by the state within the Adirondack Park. In 1923, Apperson briefly ‘kidnapped’ Governor Al Smith, taking him on a lengthy boat ride in order to convince him to stop construction of the Tongue Mountain Highway proposed by the powerful urban planner, Robert Moses. It worked. That same year, Smith appointed Apperson to the New York State Committee on State Park Planning. Apperson advanced a crusade to protect the privately owned land in the Adirondack region of Lake George from commercial exploitation. Throughout the ’20s, he convinced property owners to sell or donate lands to the Forest Preserve. By 1930, Apperson’s effort had added thousands of acres in the Lake George area. After repeated disappointments in the compromises made by existing conservationist organizations, in 1930 Apperson founded and presided over his own Forest Preserve Association. In 1931, Apperson persuaded Governor Franklin Roosevelt to expand the Adirondack State Park’s ‘blue line’ to include Lake George, the Sacandaga Reservoir, and parts of Lake Champlain. Apperson was in his full activist stride.

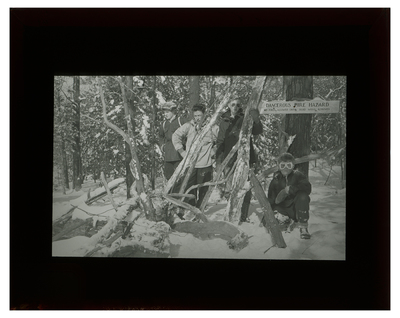

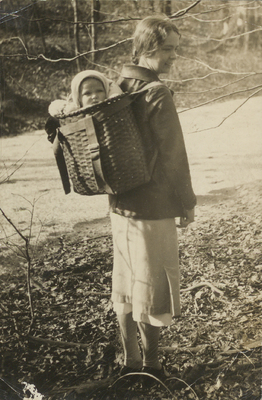

Apperson was convinced that if more people were physically and emotionally connected to the beauty the Adirondacks, they would flock to the preservationist cause. In 1914, Apperson began leading winter expeditions with college students.

Four years later, he persuaded the executives at General Electric to establish a free camp for the company’s female employees and family members in French Point on Lake George.

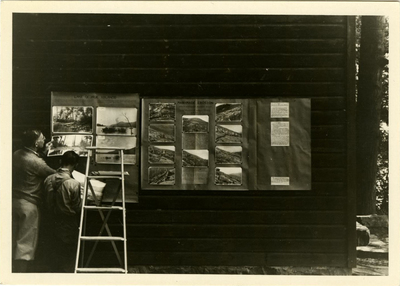

In 1922, Apperson and fellow conservationists founded the Adirondack Mountain Club. He also embraced the power of documentary photography. He mailed copies of his photographs far and wide, utilized slides at increasingly more frequent speaking engagements, and lent copies of his visual materials to any ally in need. Apperson and Irving Langmuir expanded this effort to motion picture films around 1920.

During this time, documentary photography and filmmaking were becoming increasingly effective tools for shaping public opinion. Apperson embraced this new media, launching visual campaigns that allowed him to communicate his vision to the masses. These efforts were successful, and countless new members joined the cause, including Paul Schaefer, the man who would take up Apperson’s mantle, help revolutionize wilderness political theory, and lead thousands in protecting the Adirondacks through the 20th century.

1 Speech, John S. Apperson Jr. to the Adirondack Mountain Club Conservation Committee, 1922.

2 Essay to Apperson, R. H. Doherty, August 28, 1918.

Schaefer had been interested in conservationism from an early age. In 1919, when he was 11 years old, Schaefer attended a wildlife film and lecture on conservationism at Schenectady High School given by two of Apperson’s associates, Conservation Commissioner George Pratt and Warwick Carpenter. At the end of the lecture, Carpenter gave the young Schaefer a gold pin after the boy said he wanted “to be identified with the conservation movement”.1 Schaefer was hooked.

Both of Schaefer’s parents, Peter and Rose, were intelligent, educated, devout Catholics, and outdoor enthusiasts who suffered from deteriorating health. Peter had become a skillful mountain climber while studying for the priesthood before his health failed. Rose was an accomplished vocalist in the Church. She was also a practicing nature writer, but she suffered from multiple illnesses, including tuberculosis.

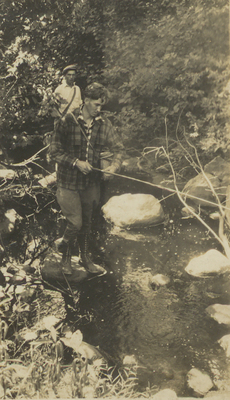

In 1921, the Schaefer family began summering in a rustic Adirondack cabin near Bakers Mills. They hoped the move would improve Rose’s pulmonary health. It also brought the family closer to the hospital where she was receiving treatment. During their summers in the wilderness, Rose taught her children about the spiritual element of nature and the importance of wild places. She broached these subjects through the teachings of St. Francis of Assisi, Romantic literature, and the encouragement of outdoor explorations of any kind: hiking, snowshoeing, hunting, fishing, or trapping.2 Paul “thrived in this wild country”.3

Over the next two years, while Schaefer’s passion for the wilderness grew, his parents’ health dwindled. In 1923, at the age of 15, Schaefer left high school to work as an apprentice carpenter in order to help cover his parents’ rapidly mounting medical bills. The drudgery of his apprenticeship made Schaefer hunger for the Adirondack wilderness. He began hitchhiking to the forest on weekends and decided to form a personal library about the Adirondack region.4 The first volume was a an autographed copy of Verplanck Colvin’s A Report on the Topographical Survey of the Adirondack Wilderness, paid for in multiple installments.

A voracious reader and bibliophile, Schaefer consumed every publication about the Adirondacks and the wilderness he could find. His library5 did not discriminate between technical volumes on natural science and environmental literature and philosophy by the likes of “John Burroughs, Henry David Thoreau, Francis of Assisi, and Viscount Francois Rene de Chateaubriand”.6 Soon Schaefer started writing nature essays and poetry of his own. In 1929, Schaefer joined the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club. Founded by Apperson and Vincent Schaefer, the organization promoted an appreciation of the outdoors and encouraged conservation.

1 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 200.

In 1930, both houses of the New York State legislature passed two of the “worst bills for Forever Wild since 1915”1: the Hewitt Reforestation Amendment and the Porter-Brereton Recreation Amendment. Because the Forest Preserve is protected by the New York State Constitution, the final decision on any alteration to Forever Wild, Article VII, Section 7, is voted on by the people of New York in a general election. The Hewitt Reforestation Amendment, dubbed the “Tree-Cutting Amendment” by Apperson, was strongly opposed by the preservationist crowd. The amendment would have permitted the state to lumber the lands surrounding the Adirondack State Park. The Porter-Brereton Recreation Amendment, better known as the Closed Cabin Amendment (CCA), would have allowed for the “clearin[g] of timber” within the Forest Preserve for the construction of “recreational facilities”.2 New York State was facing pressure from commercial interests to develop the Adirondacks before the upcoming 1932 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid.

The CCA utilized the intentionally ambiguous language of “recreational facilities” in an attempt to obscure its objectives. Initially, the CCA received mixed opinions; not all conservationists saw the construction of “recreational facilities” as dangerous to the Forest Preserve. Many thought the addition of publicly owned closed cabins or yurts would open the Preserve to wider audiences and enhance the people’s ability to enjoy the Park. Through a close reading of the bill, however, Apperson was able to see that this amendment would allow the State to log in the Forest Preserve under the guise of building “recreational facilities”.

Furthermore, Apperson discovered that this term applied not just to closed cabins and yurts, but concession stands, dance halls, ski lodges, swimming pools, or any other structure associated with recreational activities. Incensed by the threat posed by these bills, Schaefer set out to “find the best man qualified to talk to me about conservation”3 so that he could join the fight. This search led the 23-year-old Schaefer and five other members of the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club to Apperson’s front door.

John Apperson, 53 at the time, had long been mentoring young conservationists. After first gaging the group’s interest and commitment to the cause, Apperson began explaining the complicated history and current state of conservation in both New York and the nation. Fascinated by the “enthusiasm, knowledge, and perception” of the “man who understood conservation and what it took to win a fight”4 Schaefer and his cohorts pledged allegiance to Apperson, stating “we consider it a privilege to walk behind you fighters for the wilderness, ready and eager to carry the torch”.5 Their first task was to distribute Apperson’s pamphlet against the Hewitt Amendment, “Tree Cutting with Your Money,” to as many people as possible. Apperson soon deployed Schaefer and other members of the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club into the park with cameras to document the destruction of the wilderness for use in Apperson’s films and pamphlets.

1 Correspondence, John S. Apperson Jr to Fred Saunders, April 1930.

2 Porter Recreation Amendment,” High Spots, July 1931.

3 Draft forward to proposed book J.S. Apperson: Adventures in the Preservation of Lake George, Paul Schaefer, undated.

4 Ibid.

5 Correspondence, Paul Schaefer to John S. Apperson Jr., September 22, 1931.

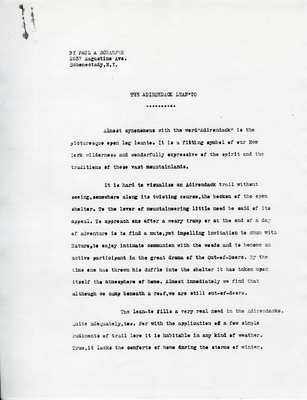

Throughout the fight against these amendments, Apperson became increasingly impressed with Schaefer’s innate skills. Schaefer had a natural gift for bringing people together, which when combined with his enthusiasm, patience, and rhetorical skills, turned many influential conservationists against the CCA. In 1931, Schaefer published an essay, “The Adirondack Lean*to”, with compelling criticisms against the amendment. Schaefer argued that the construction of resort or furnished cabins would “open avenues of chaos”1 that would soon “become commercialized and exploited for selfish interest”2. Additionally, Schaefer contended that these types of “recreational facilities” would rob people of the ability to “meet Nature on even terms”3. After months of lengthy correspondence, Schaefer brought hundreds of conservationists to the fight when he was able to shift Russell Carson, the president of the Adirondack Mountain Club, against the CCA.

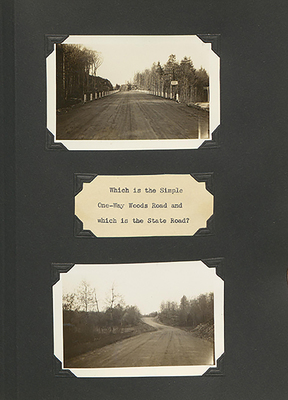

By 1932, more than 150 sportsmen’s groups and conservation organizations from around the Northeast had been united under Apperson and Schaefer against the CCA.4 In the months leading up to the 1932 general election, members of Apperson and Schaefer’s coalition published articles, delivered public speeches, and mailed thousands of pamphlets to New Yorkers throughout the state.5 Their argument was simple: The CCA was unnecessary, as hundreds of hotels, boarding houses, dance halls, and ski lodges already existed on private lands within the Park. Additionally, both primitive camping spots and camping spots with car access and modern facilities already existed within the park.6 On November 8, the people of New York voted down the Closed Cabin Amendment by a 2:1 margin.7

By 1932, Apperson had adopted Schaefer as his conservation protégé. Schaefer watched Apperson:

pursu[e] his devotion methodically, like the engineer he was, disdaining sentimentalism and vague rhetoric for hard facts. Before he wrote a stinging letter to a state official or presented a statement at a public hearing he spent days going over the site of controversy, grasping details of law and topography that often put ‘experts’ to rout.8

Apperson encouraged Schaefer’s emergence into the spotlight of the conservation debate. In the coming years, Apperson emboldened Schaefer’s growing confidence and advised him on gathering data to firmly ground his arguments. However, it was not until the impending conflict over truck trails that Schaefer truly found his voice.

1 Paul Schaefer. The Adirondack Lean*To, 1931.

2 Correspondence, Paul Schaefer to Samuel H. Ordway, December 7, 1931.

3 Paul Schaefer. The Adirondack Lean*To, 1931.

4 Opposition to the amendment was supported by Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Henry Morgenthau, Herbert H. Lehman, Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, Professor Ralph S. Hosmer of Cornell University, Dean Hugh R. Baker, Professor Nelson R. Brown of Syracuse University, Ellwood R. Rabenold, NY Chapter of the Society of American Foresters, The Mohawk Valley Towns Association, the New York Chapter of the Appalachian Mountain Club, the New York Division of the Izaak Walton League of America, Mr. WIlliam B Greekly, the Schenectady County Conservation Council, The Camp Fire Club of America, over 3,000 farmers, The Women’s City Club of New York, The Adirondack Mountain Reserve, the Mohawk Valley Hiking Club, the Garden Club of America, and others. See: Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, “State Wide Opposition to the ‘Recreation Amendment.” President’s Report, June 9, 1932 .

5 Paul Schaefer to Mr. Carson, July 22, 1932.

6 “Mountain Club Hits Proposal,” The Schenectady Gazette, January 28, 1932.

7 Vote was on November 8, 1932. 393,542 YES, 1,326,599 NO, 2,749,602 Blank! See: “Vote of the State of New York on Amendment Number

1: use of forest Preserve for Recreation Purposes.”

8 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 173.

In 1933, Conservation Commissioner Lithgow Osborne, on the advice of foresters, decided to carve a series of fire truck trails into the Forest Preserve using the Civilian Conservation Corps and a newly developed technology: the bulldozer. The majority of conservation organizations, including the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks, supported Osborne’s truck trails as a means of fire suppression. Apperson and his “coterie of Schenectady preservationists who formed the core of his Forest Preserve Association”1 vehemently opposed the trails. They argued that instead of bolstering the Park’s fire safety, the truck trails would attract private vehicles, transforming them into wilderness highways waiting to be set ablaze by an errant spark or cigarette.

Apperson was joined in his uphill battle against the fire truck trails by Bob Marshall. Son of Louis Marshall, the author of Forever Wild and a longtime Apperson ally, Bob Marshall rose to become one of the modern conservation movement’s most charismatic figures. During the early 1930s, Bob Marshall developed a ‘pure wilderness’ philosophy which stemmed from the writings of Thoreau, Muir, William James, Sigmund Freud, and Carl Jung.2 The founder of The Wilderness Society in 1934, Marshall espoused a philosophy that love of and belief in the wilderness was “not a frivolous ideal of the privileged class, but a necessity in the modern world”3 where “civilization has warped us”.4

Reinforcing Apperson’s case against the fire truck trails, Marshall added his own empirical arguments gathered from his concurrent fight against fire truck trails in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. More importantly, however, Marshall was the first to enter a purely ideological opposition into the mainstream of Adirondack environmental politics. His objections stemmed from an assertion that the truck trails would “destroy the character of the Adirondack’s wild forest lands”.5

Marshall’s argument may not seem revolutionary today, but at the time even the most staunch or radical preservationists framed all of their arguments around an empirical, scientific, or economic framework. By making this argument, Marshall was asserting that “neither timber nor soil nor humans’ need for recreation should be the focus; rather, wild nature should be considered a resource in its own right”.6 Marshall and Apperson collaboratively led the campaign against the truck trails before finally defeating the measure during the 1938 Constitutional Convention.

During his formative years as an activist, Schaefer had the opportunity to observe two giants of the conservation movement, Apperson and Marshall. From his front row seat, Schaefer watched two distinctly different approaches: While Marshall was philosophical and ideological, Apperson was experiential and pragmatic. Mentored in these two different styles, Schaefer was able to find his own voice as a defender of the wilderness.