Early Battles

In the early 1900s, John Apperson’s love of Lake George turned the young General Electric employee into an environmental activist, as he witnessed firsthand the threats posed to the area by squatters, unregulated development, and political favoritism. A passionate advocate, diligent worker, and skillful organizer, Apperson is credited with reshaping environmental politics for New York State and the nation.

A lake is a landscape’s most beautiful and expressive feature. It is Earth’s eye; looking into which the beholder measures the depth of his own nature.

-Henry David Thoreau, Walden1

Until the mid 19th century Lake George, at the southeast base of the Adirondack Mountains, was sparsely populated by family farmsteads and subsistence loggers. During this time, the introduction of new, easy and cheap transportation, factories and lumber mills arose in the area. Thomas Cole’s illustrations for James Fennimore Cooper’s 1826 bestselling novel The Last of the Mohicans also popularized the area. Crowds of tourists soon swarmed the shores of the lake. A booming tourism industry emerged, and the wealthy began purchasing the lakeside real estate that had been ignored by the local farmers because of its limited agricultural value.

The lake’s shorelines rapidly developed to house hotels, sanitariums, summer camps and personal ‘camps’. Unique to this region, an ‘Adirondack camp’ is a “permanent summer home where the fortunate owners assemble for several weeks each year and live in perfect comfort and even luxury, tho [sic] in the heart of the woods, with no very near neighbors, no roads and no danger of intrusion”.2 The grandest camps, known as ‘great camps,’ formed Millionaires’ Row near Bolton Landing and Diamond Point on the shoreline. Although they were referred to as ‘cottages,’ they were in fact palatial homes, as large as 20,000 square feet and situated on large tracts of landscaped property with luxurious amenities such as private tennis courts. The juxtaposition between the region’s older, rural, hardscrabble, agricultural inhabitants and the new influx of urban upper- and middle-class summer residents radically changed the region’s demographic climate. Both the tourism and logging industries demanded a seasonal workforce, pulling locals from their farms and flooding the woods with migrant camps.

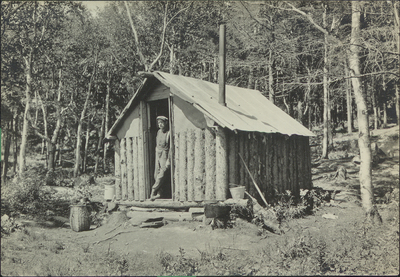

Prior to the establishment of the Forest Preserve in 1885, it was legal to reside on state land in the Adirondacks. This practice allowed residents to avoid paying property taxes on their homes. These ‘squatters’ camps spanned the socioeconomic spectrum. Some of them were composed of migrant workers’ shanties and lean-tos. On the other hand, many of the Lake George squatters were from among the wealthiest residents of Gilded Age New York: Collis Huntington, Andrew Carnegie, John Boyd Thacher, William d’Alton Mann3, and Robert J. Collier among many others4. These wealthy families erected palatial summer homes on “the most desirable… sites”5 of publicly owned land. It was an open secret that these families, although they had no valid deed to the land, had a “right” to be there by virtue of “knowing the right politician”.6 Thirty years after the 1885 law, more than 600 squatters’ camps illegally remained in the Adirondacks.7

1 Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. (London: Dent) 1910: 441

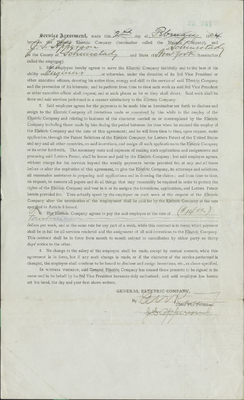

It was on this stage that in 1900 John S. Apperson Jr. (1878-1963), a Virginia native transplanted to Schenectady, New York, first set eyes on the region he would devote the rest of his life to protect. When Apperson was 16, he enrolled in the Electrical Engineering department of the Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College (now Virginia Tech), and, after only two years, dropped out to work as a railroad foreman. Drawn to the promising innovation of the newly formed General Electric Company (G.E.), Apperson moved to Schenectady, New York, with dreams of joining the company. During his first year as a New Yorker, Apperson, a dedicated outdoorsmen and canoe enthusiast, explored the Hudson and Mohawk rivers around Schenectady as well as more remote locations around the Adirondacks and Upstate region.

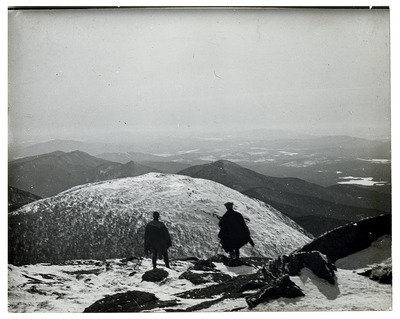

In 1900, Apperson made the approximately four-hour journey to Lake George for a canoe race. He was struck by the lake’s pristine beauty and enthralled by the hundreds of islands dotting its surface and the wild forests surrounding its shorelines. From that moment on, Apperson began visiting Lake George as often as possible. In 1904, Apperson joined G.E. as a patent engineer. With more disposable income, Apperson began visiting the lake year round and experimenting with the thrilling winter sport of skate sailing. By 1907, Apperson was traveling to Lake George on a weekly basis.

In the summer of 1902, Apperson set up a tent in a public campsite on state-owned Dollar Island. With a canoe and a map, the 24-year-old Apperson set off to explore the publicly owned Forever Wild lands. Almost immediately, he encountered squatters. Apperson initially viewed them as a nuisance, an irritating encroachment on what should have been uninhabited wilderness. Over the years, he grew to despise the expansive estates, wastefulness, and lavish parties thrown by the wealthy squatters. Apperson regarded the squatters’ illegal appropriation of protected, publicly owned land as antithetical to the wilderness experience and blasphemous to Forever Wild. Always armed with a camera, Apperson began photographing every squatter he encountered.

The squatters controversy marked a turning point in Apperson’s life. Prior to this, he has been a staunch individualist, drawn to the wilderness where “spiritual truths are least blunted.”1 He had not been participating in the conservationist dialogue. But now he found the intrusion of the squatters in the public wilderness to be intolerable, and he began to educate himself on conservation law and politics, in part by studying law books at the Albany Law School. Now his love of the region was combined with a new understanding of the legal issues, transforming Apperson from a recreationalist into an activist. Later, Apperson would use this powerful combination in order to convert others to “his religion: conservation.2"

1 Nash, Roderick. Wilderness and the American Mind. (Yale University Press) 1982: 86

2 Newkirk, Arthur E. and Ham, Phillip W. “Forest Preserve, Lake George, and ‘Conservation’ Owe Great Debt to John S. Apperson”, Schenectady Times Union, February 5, 1963.

In 1906, Apperson noticed a significant increase in erosion on Lake George’s shorelines—so significant that some islands were in danger of washing away. In his research, he discovered that in 1903 the International Paper Company had replaced the natural stone dam on the northern outlet of Lake George in Ticonderoga with an artificial dam. This new dam succeeded in “converting Lake George into a veritable mill pond”1 by raising and lowering the lake’s water levels to power the factory. In 1904, the International Paper Company, in reaction to the residents’ protests, promised no longer to alter the lake’s water levels. It was clear to Apperson that they had reneged on their word.

Apperson wrote an editorial for the Lake George Mirror calling for an immediate remedy: the reconstruction of the natural dam at the lake’s original outlet and the demolition of the International Paper Company’s artificial dam. Apperson attempted to present data on the water levels to the Lake George Association, urging them to address the issue. His pleas were ignored on the grounds that he did not own private property in the region. Water levels continued artificially to fluctuate, damage to the delicate shorelines escalated, and Apperson’s 47-year battle to protect Lake George from the International Paper Company had begun.

In 1909, he took matters into his own hands. The deterioration of the islands on Lake George had become so severe that something had to be done to mitigate the destructive forces of the fluctuating water levels. Apperson began ‘riprapping’ Lake George’s islands. Riprapping is a process of using large stones to provide a foundation in order to reinforce shorelines against water erosion. He began with Dollar Island, his longtime campsite. Apperson transported each large stone by hand across the lake in his canoe before placing it on the shoreline. The work was time consuming and physically demanding.

Although Apperson had first encountered the Adirondack region as a consummate backwoods loner, the circle of people around him was growing steadily. Apperson cultivated important allies with local property owners and state representatives by sharing his Lake George photography and by writing insightful letters on environmental issues. Over time, he formed bonds with fellow G.E. employees who shared his outdoor interests. In 1910, Apperson met Irving Langmuir, a newly hired chemist who would go on to win a Nobel Prize in 1932. The two were immediately inseparable and would remain so until Langmuir’s death in 1957. Apperson infected Langmuir with “Lake-Georgeitis…loyalty to Lake George and its environs”.2 Langmuir’s gregarious, New York personality complemented Apperson’s southern charm and sly sense of humor.

1 Apperson, John S., Editorial in Lake George Mirror. July 21, 1906.

2 Rosenfeld, Albert. The Quintessence of Irving Langmuir. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1966: 198

Soon, Apperson and Langmuir were joined by a cadre of G.E. employees on many of their Lake George adventures. Practical by nature, Apperson instituted a rule that each visitor joining them on the lake was required to bring at least one stone per person for the slow work of riprapping the island shorelines. This rule lead to a collaborative buy-in for Lake George’s preservation needs among many of the G.E. employees. It was also the beginning of Apperson’s Associates—known by many in the conservationist circle as the “Schenectady Force”.1 Apperson organized riprapping parties with locals, Schenectady tourists, and conservation organizations. Between 1909 and 1916, “three hundred and eleven people from twelve nations and twenty-seven different states”2 joined Apperson in riprapping Lake George shorelines.

On the July schedule of the 1915 New York Constitutional Convention were two amendments proposing modifications to Forever Wild, which, if ratified, would adulterate or negate the protection of the Adirondack Forest Preserve. The first amendment would allow the wealthy squatters to perpetually lease the land beneath their houses from the state, thus legitimizing and ensuring their intrusive presence on public land. The second amendment, written by the timber industry, would reclassify land in the Preserve as either a) mountaintops, streams, and rivers or b) everything else. Category A, encompassing 4 percent of the Forest Preserve, would retain all of its current protections. Category B, encompassing 96 percent of the Forest Preserve, would be reopened to logging.

Apperson was familiar with the devastating effects of the timber industry from his time as a railroad foreman in Virginia. Enraged by the prospect of legitimizing the squatters’ presence, he committed himself to protecting the Forest Preserve. Although involved in conservation activities, Apperson had never before entered the political arena. Determined to protect the Forest Preserve at the Constitutional Convention, Apperson reached out to his friends with political expertise, seeking “knowledge on procedure… [in these] entirely unfamiliar matters”.3

In the few months remaining before the vote on these proposals, Apperson cultivated and mobilized a wide base of grassroots support. He wrote letters to every known conservationist, recreationalist, and conservation organization with a detailed analysis of the impact which the amendments to the constitution could have on the Forest Preserve. He pled for support to protect “the fundamental law which safeguards our state parks”.4 In May of 1915, Apperson mobilized this support, targeting state representatives in the weeks leading up to the Convention. Apperson explained to his supporters:

We must do our part on the firing line and on the right side, and I urge every member not only to write a letter [to your representative] but talk to your neighbor and keep on talking until we are sure of adequate protection in our new constitution.5

1 Frank Graham, Jr. The Adirondack Park: A Political History. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1978): 172.

2 Correspondence, John S. Apperson Jr to Warwick Carpenter, April 18, 1916.

3 Correspondence, John S. Apperson to J. E. Sague, March 18, 1915.

4 Circular, Untitled, Apperson, John S., May 1915.

5 Correspondence, John S. Apperson to H. Lansing Quick, May 28, 1915.

Apperson was convinced that if enough people “relat[ed] [their] actual experiences” the misinformation and “confusing theories”1 used to manufacture support for the amendments would be proven false. Many high-level conservationists rallied behind Apperson, such as Conservation Committee member Olin H. Landreth (student, and later, professor at Union College), Justice Robert J. Wilkin, and famed conservationist Dr. William T. Hornaday. However, not all conservationists answered his call. Apperson wrote one of his heros, author John Burroughs, entreating him to speak against the proposed amendments at the upcoming Convention.2 Burroughs brushed Apperson aside, responding, “I am preoccupied and cannot interest myself in your matters”.3

In late June of 1915, Apperson burst into the Constitutional Convention, distributing pamphlets filled with data against the amendments, photographs “amplifying [his] purpose,”4 and testimonial letters supporting the protection of Forever Wild. At the public forum, Apperson gave a rousing speech, swaying many of the representatives to his cause. As a result of Apperson’s leadership, both amendments were defeated. On July 28 of that year, Dr. Hornaday wrote:

The people who hereafter will enjoy the freedom of… the Adirondacks, unhampered and unafraid of… those who are exploiting the Adirondacks for commercial purposes, will need to thank you! … This is not flattery… knowing the circumstances as I do, I am able to speak with absolute certainty of being correct. The leasing of [squatters] camp-sites was prevented by the far-sightedness, good generalship, and love-of-the-open… of J. S. Apperson!5

With the momentum of his victory at the Constitutional Convention, Apperson made a series of strategic moves: He secured state funding for the riprapping of Lake George’s islands, he began personally evicting the Lake George squatters, and he started advocating for the creation of a Lake George National Park. Apperson also created a 47-page booklet to deliver to the 1917 session of the New York Legislature. The first nine pages contained a photojournalistic layout that illustrated the distressing condition of state-owned islands and the positive effect of riprapping. The book also described the success of his previous riprapping and the need to continue these efforts. The booklet also strongly urged the legislature to enforce regulations on artificial water fluctuations on Lake George. Finally, it recounted continuing problems with the “most antagonistic” squatters who continued to claim entitlement to their illegal estates “because of their political connections.” 6 This booklet succeeded in securing a $10,000 appropriation for the riprap of Lake George islands. Apperson expanded the impact of this fund by persuading shore owners and the D&H Railroad to donate labor, barges, and money to the cause.

1 Ibid

2 Correspondence, John S. Apperson to John Burroughs, May 19, 1915.

3 Correspondence, John Burroughs to John S. Apperson Jr., May 20, 1915.

4 “New York Supreme Court Record on Appeal, New York State et al v. System Properties et al, Volume 1.”

5 Correspondence, William T. Hornaday to John S. Apperson, July 28, 1915.

6 Correspondence, David Rushmore to C. R. Pettis, Superintendent of Forests, July 6, 1917.

Apperson and his associates began evicting squatters in 1916 and continued until the early 1920s. Apperson’s methods were direct and contentious. Arriving unannounced to the illegal camps, Apperson and his associates served the squatters with legal eviction papers. Most of the squatters refused to heed the eviction notices and threatened Apperson with physical violence or political retribution. Undaunted, Apperson countered that if they did not leave, he and his associates would return the next week and take down their illegal camps, regardless of occupancy. Both parties upheld their threats.

True to his word, Apperson and a crew of preservationists would arrive a week later on his barge, aptly named “Article VII, Section 7”. Armed with sledgehammers, they disassembled the wealthy squatters’ estates and removed them from public land. The Schenectady Force ripped siding, shingles, and porches off of houses, whether they were occupied or not. They dismantled entire estates before floating the salvage, along with the squatters, off of the public land. The squatters’ threats against Apperson’s safety were real. Although no anecdotal accounts remain within his papers, Apperson applied for a pistol permit in 1918, citing fear for his safety in the backwoods. Some of the squatters Apperson evicted were top-level executives at G.E. In 1922, after 18 years with the company, Apperson was fired without explanation. Irving Langmuir, one of G.E.’s star scientists, petitioned unsuccessfully on Apperson’s behalf within the company.

Finally, after eight months, Langmuir threatened to quit if Apperson was not reinstated. Ultimately, G.E. rehired Apperson, placing him in an administrative position. Apperson’s devotion to Lake George and the Forest Preserve was unparalleled. Conservation became “his religion,”1 and Apperson declared that “Lake George is my wife, and the islands our children”.2 Although Apperson was never able to instigate the founding of a Lake George National Park, he did succeed in persuading Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt to expand the Adirondack State Park to encompass the region in 1931. For the remainder of his life, Apperson served as the “dean of the implacable conservationist who wanted the woods as God made them”.3 Apperson also educated a new generation of conservationists on fearlessness, uncompromising ideals, and effective tactics. Throughout the course of the 20th century, he and his protégés tipped the balance of power away from commercial interests and reshaped environmental politics in New York and the nation.

1 Newkirk, Arthur E. and Ham, Phillip W. “Forest Preserve, Lake George, and ‘Conservation’ Owe Great Debt to John S. Apperson”, Schenectady Times Union, February 5, 1963.

2 “New York Supreme Court Record on Appeal, New York State et al v. System Properties et al, Volume 1.”

3 Fowler, Barnett. “State Conservation Leader Buried” Times Union (Albany, New York), February 10, 1963.