Black River Wars

In the 1940s and 1950s, Paul Schaefer led a dedicated group of conservationists against the power industry in an attempt to prevent the construction of dams in the Adirondacks. Schaefer’s campaign was an effective blend of media, education, legal arguments and political savvy that resulted in a victory which created a model for environmental activism that has been adopted by conservationists across the country.

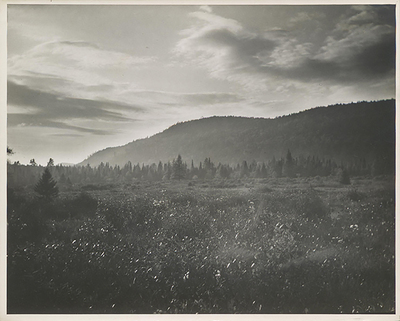

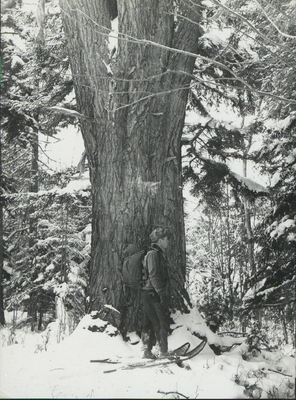

A citizen may not have the title to his home, but he does have an undivided deed to this Adirondack land of solitude and peace and tranquility. To him belong the sparkling lakes tucked away in the deep woods and the cold, pure rivers which thread like quicksilver through lush mountain valleys. His determination to preserve his personal treasure for posterity has been tempered by memories of campfires, and strengthened by pack-laden tramps along wilderness trails and by mountaintop views of his chosen land. To him the South Branch of the Moose is a River of Opportunity, for he has come to regard it as the front line of defense against the commercial invasion of his Forest Preserve.

-Paul Schaefer1

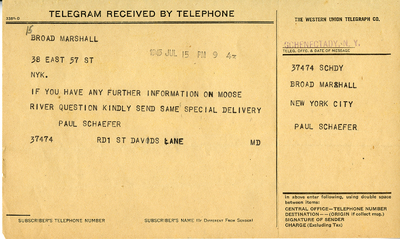

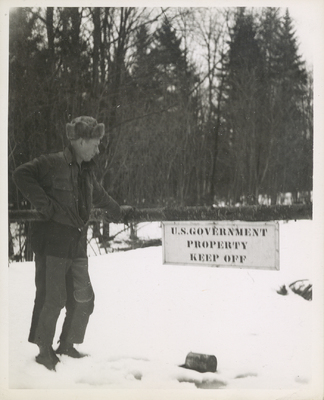

For nearly three decades, plans for a series of 38 reservoirs across the Adirondack Region silently slipped through the eddies of New York State’s Department of Conservation. By 1942, construction was slated to begin2 on the first two dams on the Moose River at Higley Mountain and Panther Mountain. Together, these two dams would have flooded the Moose River Plains within the Forest Preserve. It was not until late 1944, when Paul Schaefer noticed illegal logging on the Panther Mountain dam site,3 that the existence of these projects came to the attention of conservationists. From 1945 until 1956, Schaefer led the charge against the dams in one of the largest and most successful grassroots environmental campaigns in legal history. They would become known as the Black River Wars.

The story of how the proposed dams and reservoirs eluded the watchdogs of the Forest Preserve is complex and bureaucratic. In 1913, the Burd Amendment modified the language of Forever Wild, Article VII Section 7, of the New York State Constitution, giving “constitutional sanction to limited encroachment on the Forest Preserve”4 via the “construction and maintenance of reservoirs for municipal water supply, for the canals of the state and to regulate the flow of streams”5.

The Department of Conservation was given the management of this task. They, in turn, redirected the oversight of water regulation to the Water Power and Control Commission. In 1915, the Machold Storage Law was passed, allowing any property owner, private or municipal, the ability to petition the Water Power and Control Commission to form a “river regulating district”. Comprised of three people appointed by the Governor, a river regulating district held the power of both a public corporation and a state agency with the authority to exercise eminent domain, assessment, and taxation.6

1 Schaefer, Paul. The Forest Preserve, No. 3 (July 1948) 3-4

2 Correspondence, E. S. Cullings to Grace L. Hudowalski, undated.

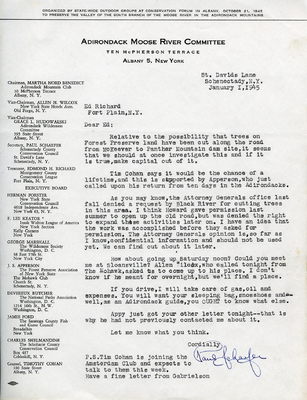

3 Correspondence, Paul Schaefer to Ed Richard, January 1, 1945.

4 Martin, Roscoe Coleman. Water for New York: A Study in State Administration of Water Resources. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press) 1960: 147.

5 N.Y. Const. art. XIV, § 2 (Amended from N.Y. Const. art. VII, § VII)

6 Martin, Roscoe Coleman. Water for New York: A Study in State Administration of Water Resources. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press) 1960: 147-148.

In 1919, the first river regulating district to form was given dominion over the Black River Basin, where the delicate ecosystems of the Moose River Plains are located. The Black River Regulating District (BRRD) was staffed with members of the power industry and work began immediately on a series of hydroelectric dams across the Adirondack region. Between 1920 and 1941, the BRRD conferred with the Water Power and Control Commission on plans for the construction of dams and reservoirs. On November 25, 1941, a plan for two hydroelectric dams on the Moose River, a tributary of the Black River, was submitted to the Water Power and Control Commission. They approved the project on May 2, 1942 after a quietly advertised public hearing.1

When Paul Schaefer learned about the proposed dams, he immediately recognized the significant dangers posed to the Adirondack wilderness. By then, he was an educated and connected conservationist. Together with Edmond Richard, a fellow Apperson protégé, Schaefer reached out to his preservationist allies for help in this “chance of a lifetime”2 for environmental activism. Schaefer and Richard approached Conservation Commissioner Perry Duryea for advice on stopping the proposed dams in the Forest Preserve. Duryea’s response was disheartening and direct: “You’re too late… the fight’s over”.3 No means of legal appeal existed within the Conservation Department’s structure4 and the Water Power and Control Commission would resist any effort to revisit already approved proposals.5

Schaefer and Richard turned next to the longest-standing conservation organization in the state, the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks. After contacting the Association’s president, Frederick Kelsey, Schaefer and Richard traveled from Schenectady, New York, to the Association’s headquarters in New York City. Armed with slides illustrating the impending devastation to the region, Schaefer and Richard gave a half-hour presentation to the Association’s Board of Trustees pleading for their help in “turning this thing around”.6 Their reply was devastating to the two conservationists: “We’d like to help you… but the Association is not used to being involved in lost causes”.7

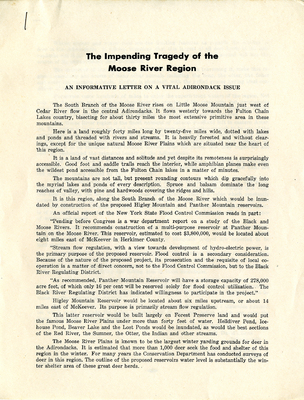

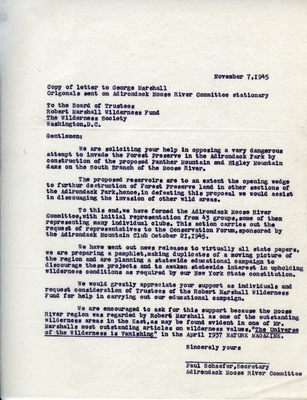

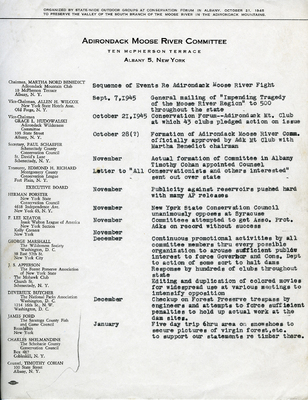

Recognizing that establishment conservation organizations were not going to support their “lost cause,” Schaefer and Richard went to work on a grassroots campaign. Schaefer attended meetings across New York State and wrote passionate letters to every sportsman, hunter, nature lover, Adirondack resident, and influential member of the environmental community in his address book. Over the course of 10 months, their campaign was successful and opposition to the proposed dams grew steadily. Schaefer and Richard drafted the persuasive essay “The Impending Tragedy of the Moose River Region,” strategically mailing nearly 1,000 copies throughout Upstate New York one month before the upcoming Annual Conservation Forum in Albany.8 On October 21, 1945, at the Forum, Schaefer and Richard made a successful presentation about the dams, securing the pledged support of 43 environmental organizations and hundreds of individuals.9

1 The Adirondack Moose River Committee. “Moose River Brief: What’s It All About”; “Memorandum from William R. Adams, President of Black River Regulating District”; Correspondence, E. S. Cullings to Grace L. Hudowalski, undated.

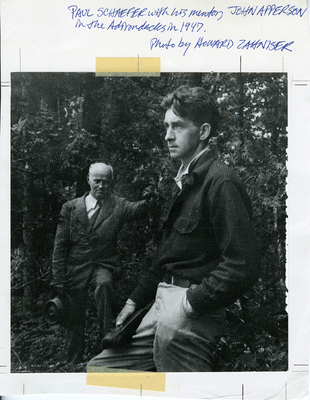

The Adirondack Moose River Committee (AMRC), with Richard as President and Schaefer as Secretary, was also formed for the purpose of “preventing the destruction by flooding of the valley of the South Moose River and other similar lands in the Adirondack Mountains, and to disseminate information about such flooding projects”.1 Schaefer staffed the AMRC’s executive board with many influential members of the preservationist community: John Apperson of the Forest Preserve Association, Devereux Butcher of the National Parks Association, Herman Forster of the New York State Conservation Council, and George Marshall of The Wilderness Society.2

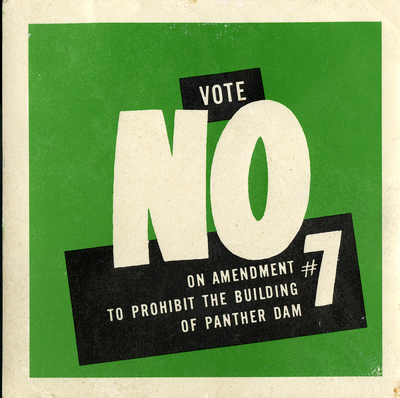

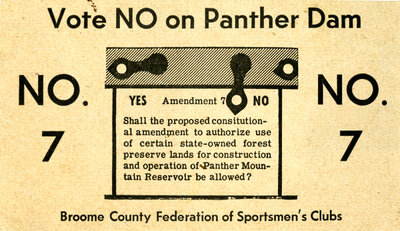

It was a formidable group. During their tenure, they developed and advanced legal, environmental, and ethical objections to the dams. The thousands-strong membership of the AMRC challenged the BRRD in the courtroom, in the legislature, and in the press. The AMRC also circulated innumerable pamphlets, stickers, and postcards utilizing an AMRC youth corps to deliver circulars to the most remote residents of the Adirondack region.

During the struggle against the Closed Cabin Amendment in the 1930s, Schaefer found that his “connection to Nature Magazine proved a vital factor in the defeat… because of the number of articles that it published on our behalf”.3 In 1947, he persuaded the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks (which was now part of the AMRC) to begin publishing The Forest Preserve magazine. Schaefer held the role of editor for 11 years. During the Black River Wars, he wrote eloquently in each issue about the intrinsic value of the wilderness region and “the remarkable exhibition of dictatorial power… by the Black River Regulating District” as they endeavored to “to invade your Forest Preserve”.4

The argument advanced by Schaefer from his editorial bully pulpit at The Forest Preserve was revolutionary. The spirit of his theories echoed the writings of John Muir, Aldo Leopold, and Bob Marshall while the fire of his beliefs reflected his education with the “dean of the implacable conservationist”,5 John Apperson. Arming himself with the New York “state constitution, Schaefer went even further”6 than his forefathers. In writing on the proposed destruction of the Moose River Plains, Schaefer stated that “the issue concerns [one’s] basic human rights as a citizen of New York State”.7 Schaefer was espousing a new wilderness philosophy: Wilderness as a civil right.

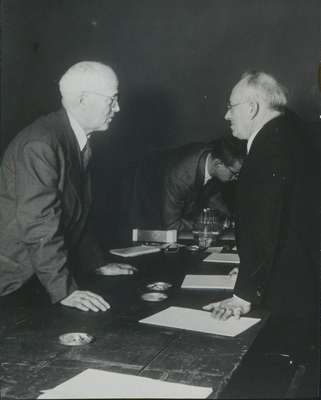

Leo Lawrence, the chairman of the Legislative Assembly, introduced the Lawrence Act, which would block construction of the additional 36 proposed hydroelectric reservoirs within the Forest Preserve and give the people the power to vote on all future flooding projects on public land.8 Apperson aggressively lobbied for this bill, collected data on the economic and environmental effects of the proposed dams, and actively refuted all inaccurate claims in the media.9 The Lawrence Act passed the New York House of Representatives, but was narrowly defeated in the Senate.

1 Adirondack Moose River Committee, “Statement of Purpose.”

2 Adirondack Moose River Committee “Member List”.

3 Schaefer, Paul. Adirondack Explorations: Nature Writings of Verplanck Colvin. (Syracuse University Press, 1997): xiv-xv.

4 Editorial. Schaefer, Paul. The Forest Preserve. 1953.

5 Fowler, Barnett. “State Conservation Leader Buried” Times Union (Albany, New York), February 10, 1963.

6 Paul Schneider, The Adirondacks: A History of America’s First Wilderness. (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1997): 294.

7 Schaefer, Paul. The Forest Preserve, No. 3 (July 1948) 6

8 New York (State). Legislature. Assembly. An act to amend the conservation law, in relation to prohibiting the construction of new... 1076 – A. 1947-1948 Reg. Sess. (January 30, 1947).

9 John S. Apperson to the Watertown Daily, January 9, 1947.

In 1947, Governor Thomas Dewey reached a backroom agreement with the BRRD. Up until this point, the AMRC had focused the majority of its attack on the Higley Mountain dam, as the Panther Mountain dam would not begin until the construction at Higley Mountain was complete. In a clandestine meeting, Dewey and the BRRD agreed that Dewey would halt the Higley Mountain dam without protest from the BRRD. In exchange, the BRRD would gain Dewey’s strong support for a greatly expanded Panther Mountain dam.1 In November of 1947, Dewey halted the Higley Mountain dam, and in December began supporting the newly enlarged project at Panther Mountain. To support his position and to push for a special assessment tax which would fund the BRRD’s project, Dewey argued that an electrical deficit was imperiling New York. 2

In response to Dewey’s actions, the Forest Preserve Association released a pamphlet stating that “the seriousness of this interference… and the growing arrogance and power of the hydro-electric interests indicates even more tentacles are sprouting on the power octopus,”3 infiltrating the government, and denying the people of New York their rights. The public outcry was immense and hundreds of organizations, including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, joined the ranks of the AMRC. The Adirondack League Club, a private conservation club and member of the AMRC, owned a large tract of property within the proposed flood zone. In concert with the AMRC, the Club sued the BRRD in 1948. During this three-year lawsuit, the activists put forth two main arguments: that the dams were unconstitutional and that they went against the public interest.

According to the AMRC, both dams were in direct violation of the 1913 Burd Amendment of the New York State Constitution, because the BRRD publicly stated that the development of hydroelectric power was the primary goal of the Higley and Panther Mountain dams.4 The Burd Amendment explicitly restricted the purposes for which water could be controlled to the creation of municipal drinking water and the regulation of the state’s canal system.5 Additionally, the AMRC argued that the BRRD violated the constitution by knowingly misleading the public and that they would overstep their authority to exercise eminent domain by seizing land under the veil of public use, when “in reality it is taken for private use, profit and gain.”6

The BRRD argued that the local mill towns in the Moose River region were suffering from an economic decline due to droughts and unreliable water flow. The proposed dams would both stabilize and increase the current of the Moose River and revitalize the local economy. Thus, the purpose of the dams was in fact public, and the production of hydroelectricity was merely a beneficial side effect.7

1 Martin, Roscoe Coleman. Water for New York: A Study in State Administration of Water Resources. (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press) 1960: 158-9.

2 Newsletter, Adirondack Moose River Committee. December 14, 1947.

3 Pamphlet, “Flooding and Proposed Flooding of Forest Preserve Land,” Forest Preserve Association. 1948.

4 Back Water Regulating District Representative, February 26, 1947, as quoted in F. Walter Bliss, and Milo R. Kniffen.“Memorandum on Behalf of the Moose River INC: In Opposition.” 1948.

5 N.Y. Const. art. XIV, § 2 (Amended from N.Y. Const. art. VII, § VII)

6 Appellant Brief, Adirondack League Club et al v. The Board of the Black River Regulating District and William R. Adams, Alfred Stiles Jr., and Henry E. Smith constituting the Members of said Board.”

7 Memorandum from William R. Adams, President of Black River Regulating District.”

The AMRC argued that the flooding was against the public interest as the proposed dams would irreversibly destroy 4,000 acres of wild forest lands, obliterating animal habitats, offsetting species populations, and polluting the Moose River Plains’ delicate biosphere with mud, silt, and refuse.1 The BRRD countered that the steep banks of the southern Moose River and the “impassable swamp lands” 2 of the plains made the region unsuitable for animal habitat, inaccessible to hunters, and therefore of limited value.3 Furthermore, the BRRD argued that the dams would aid, not destroy, the regions’ ecosystem by controlling the impact of seasonal snowmelt flooding.4 The AMRC responded to these assertions by arguing that the flooding would remove vital small-game habitats and “seriously effect the region’s deer-carrying capacity… by reducing the amount of available winter cover”.5

The ARMC and the BRRD fought through every judicial level until a decision was reached in 1949. The New York State Supreme Court decided for the conservationists, declaring that use of eminent domain on public property for private gain was indeed unconstitutional. In 1950, Governor Dewey bowed to intense public pressure and signed into law the Stokes Act, which prohibited the construction of reservoirs on the southern branch of the Moose River. But the AMRC knew this Act alone was not sufficient. In order to remove the threat of a flooded Forest Preserve for generations to come, they would need to amend the New York State Constitution.

In 1952, Assemblyman John Ostrander introduced an amendment which “prohibited building any river reservoirs whatsoever in the Forest Preserve,” 6 effectively negating the 1913 Burd Amendment. The AMRC rallied behind this amendment by creating the Council of Conservationists for Amendment 9.7 The members of the Council pressured local, state, and national representatives leading to an

“outstanding example of bipartisan cooperation. Republicans and Democrats alike, recognizing the real public interest in this measure, forgot their differences and combined to lift the amendment out of the realm of party politics…the will of the people as expressed through their representatives asserted itself with invincible force”.8

Under Schaefer’s leadership, the AMRC scored a resounding victory at a critical moment in the history of environmental politics. The unprecedented number of diverse individuals held together for nearly a decade under one cause inspired the leaders of the wilderness movement across the nation. The victory of the Black River Wars resulted in a seismic shift in 20th century national environmental policy when it inspired Howard Zahniser, author of the 1964 federal Wilderness Act. Zahniser employed Schaefer’s methods at Utah’s Dinosaur National Park, where he defeated the Echo Dam project. He also incorporated Schaefer’s philosophy of wilderness as a civil right in drafting the Wilderness Act. From the Black River Wars until his death in 1996, Paul Schaefer displayed a remarkable level of influence and astute political acumen, as well as an ability to rally diverse groups into powerful coalitions. For half a century, Paul Schaefer’s strong leadership and ever-growing, powerful cadre of preservationists effectively battled commercial interests for legislative control of New York’s wilderness, literally changing the landscape of New York State.

![Lee [Keator] notifies Paul Schaefer on August 6, 1945, of an advertisement in the Rome Daily Sentinal concerning the sale of State lands and timber from the Highley Mountain area. The advertisement quotes a Mr. William P. Creager as consultant, a rumored associate with federal damming and constructing projects.](https://exhibits.schafferlibrarycollections.org/files/large/8698e38b69f3584d527fac4ebf38443c2e124385.jpg)